How to simplify rail fares

Learning from the one thing that German railways get right.

Only three people have ever really understood the Schleswig-Holstein business – the Prince Consort, who is dead – a German professor, who has gone mad – and I, who have forgotten all about it.

Lord Palmerston’s quip about nineteenth century geopolitics could apply with equal force to British railway fares. Why does a return sometimes cost only a fraction more than a single? What is the difference between ‘off-peak’ and ‘super-off-peak’? Why is ‘split ticketing’ possible? (It means e.g. getting one ticket from London to Didcot and another from Didcot to Bristol, rather than just one from London to Bristol) Why do you normally need to buy one ticket for the bus and one for the train? Most importantly, why are they so expensive?

A related problem is that public transport services themselves are poorly co-ordinated. A journey involving a change of trains is a lottery where often the connection will be either impossibly short or tediously long. It is even less likely that there will be a good connection with bus services.

This decreases ridership. Railways are a network, so are subject to network effects: as more stations are added, the number of potential journeys increases at a rate faster than the increase in the number of stations. This is a really useful property that railways should use to their advantage; but thanks to our byzantine ticketing system, poor-quality connections and lack of integration with buses, many of those potential journeys are either impractical or too expensive.

German speaking countries have (partially) solved this problem. I have previously written about the Swiss way of timetabling trains, to optimise for connections. But there is an even more important thing that German-speaking countries have done: the transport association, or Verkehrsverbund. (Pronunciation note: in German, ⟨v⟩ sounds like an English /f/.)

Every metropolitan region in Germany has a Verkehrsverbund: for instance, there is one for Munich and the surrounding region, one for Berlin and the surrounding state of Brandenburg, and one for the dozen or so cities of the Rhein-Ruhr area in the west of the country. The Verkehrsverbund’s boundaries therefore stretch well outside the political boundaries of the principal city they serve: they are for city regions, not just for cities.

A typical Verkehrsverbund co-ordinates fares, ticketing systems and timetables across the region. The fares are structured in a simple, zonal system, and do not distinguish between mode (so bus and train fares cost the same for the same journey), nor between different operators. The Verkehrsverbund usually also creates consistent passenger information, such as transit maps and timetables.

Crucially, however, the Verkehrsverbund does not operate any services itself. It neither owns the tracks, nor runs the trains, nor operates the buses. Within its region of service, there might be several dozen separate organisations that actually operate the services: Munich’s has 55.1 These transit operators are funded by the Verkehrsverbund, which sells tickets, and distributes the revenue to the transit operators. It also distributes government subsidies to the operators. The big transit operators are invariably publicly-owned, usually by city councils, although some of the smaller ones are sometimes private companies.

This model is somewhat similar to things that Britain already has, but there are some important differences.

In particular, Transport for London is not a Verkehrsverbund. It co-ordinates fares, but non-TfL rail services are only partially brought into the fare zone system, and TfL buses are not integrated with rail at all. Furthermore, it either operates services in its own right (the London Underground) or contracts out their operations, as it does with the Elizabeth Line, the Overground, and the buses. In the North, Transport for Greater Manchester is also moving in this general direction.2

Verkehrsverbünde have a much narrower set of responsibilities: they only co-ordinate fares, timetables and passenger information. Verkehrsverbünde also cover all of a city’s metropolitan area: Hamburg’s Verkehrsverbund serves an area of 9,693 km², while TfGM, which is responsible for a similar-sized city, only serves 1,276 km².

At a high level, this is all you need to know about Verkehrsverbünde. The rest of this (long) article goes into more detail about the Verkehrsverbund system, and then considers whether Britain should adopt the system.

(I use the German word when talking about Verkehrsverbünde as they work in German-speaking countries, and the English term ‘transport associations’ when talking about them as they might work over here.)

Where do they operate, and who runs them?

Verkehrsverbünde tend to cover the entirety of a city’s metropolitan region. That said, they do vary considerably in how widely these boundaries are drawn.

Hamburg’s Verkehrsverbund covers an area of 9,693 km², and serves a population of 3,670,000. This is just about the most maximal definition of Hamburg’s metropolitan area. Munich’s is a similar size, in terms of both population and area. Berlin, however, has a much bigger Verkehrsverbund. It covers the entirety of Berlin and the surrounding state of Brandenburg – 30,546 km², which is 50% bigger than Wales.

Crucially, there is no Verkehrsverbund that only co-ordinates transport within a city’s urban area. This is the right way to do things: it means, for instance, that a commuter from a suburban town, who transfers to the metro, only has to pay one fare. Cities and their metropolitan regions are interdependent on one another, and the boundaries of the Verkehrsverbund reflect this.

A Verkehrsverbund is not, to be clear, an association of the transit operators within its area of operation. Instead, it is an association of state and local governments. Hamburg’s Verkehrsverbund, for instance, is owned 85.5% by Hamburg (which is both a city and a state), 5% by the two neighbouring states, and 9.5% by the neighbouring districts which are served by the Verkehrsverbund.

Simple(r), integrated zonal fares

The most eye-catching feature of the Verkehrsverbund model for Britishers is that all public transport fares are integrated into a single fare structure, based on fare zones. Zonal systems are familiar to anybody who has travelled on the Tube: there is one fare for travel just within Zone 1, another for travel within Zone 2, and a third for travel within both Zones 1 and 2, and so on.

There is, however, an important difference (for a Londoner): buses and trams are fully integrated into the fare structure. In other words, there is no penalty for changing between a bus and a train. This is, again, the right way to do things. Public transport is a network, and it is to the benefit of all parts of the network if transfers are free.

Zones ensure that passengers are charged roughly based on usage: a longer journey costs more, unlike systems of flat fares, such as the New York City Subway where a single journey costs $2.90 irrespective of how long it is. Equally, zones are simple to understand for passengers, who are not charged by an arcane formula according to the precise distance they travel.

Here, for instance, is Hamburg’s zonal system. Rings A and B cover the Hamburg urban area, and for €7.80 you can buy a ticket that covers unlimited travel for a day within this area. (This compares with £8.90 per day for Zones 1–2 in London.) For unlimited travel within the whole 9,693 km² of the Verkehrsverbund, it costs €24.40. Rings C–F are subdivided into little numbered zones, corresponding to individual towns; you can buy a ticket for €2.80 that covers a single journey within one of the numbered zones.

The Verkehrsverbünde offer cost-effective season tickets. In 2022,3 a weekly ticket for Rings A and B cost €30, and a monthly subscription cost €93.70 (compared with €8.10 for a day ticket). This represents more than a 50% discount on regular usage.

Obviously, the details of the fare structure can vary, and so can the level of the fares. But there are a few general design principles:

All public transport (except possibly long-distance trains) should be integrated into a single fare structure.

The fare structure should be simple and based on zones.

There should be a substantial discount for regular users.

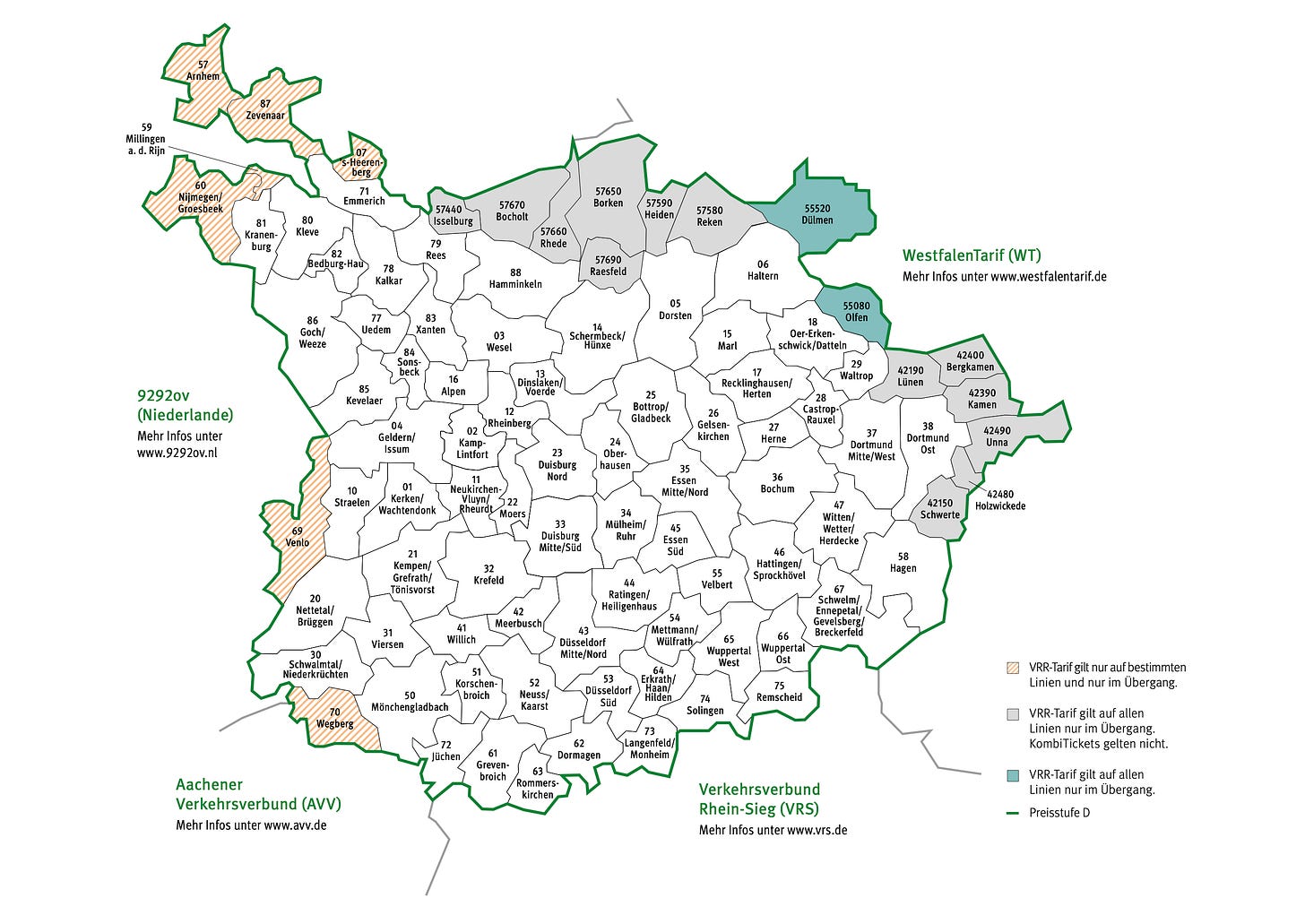

Zones do not necessarily need to be concentric, as they are in Hamburg and London. The Rhein-Ruhr region, which consists of the cities of Düsseldorf, Duisburg, Essen, Bochum and Dortmund, as well as a dozen or so smaller cities, is famously polycentric, which means there is no single point on which zones could be centred. The VRR therefore divides its area into ‘tiles’, which generally correspond to a single city. There are three fare zones: A, which allows travel within one tile; B, which allows travel within one tile and all its neighbours; and C, which allows travel across the entire region.4

This kind of tiling zonal system could work in a polycentric region like West Yorkshire.5 The region would be divided into, say, a dozen tiles corresponding to either one city, or a group of towns and their rural surroundings. This avoids having a zonal system that is overly focused around Leeds.

A tiling arrangement can also solve a problem that Germany has experienced: high and complicated zones at the boundary between Verkehrsverbünde, because the Verkehrsverbünde do not always have an incentive to co-operate with one another. Fares could be determined on the basis of the number of tiles that a passenger wishes to pass through.

Conceivably, such an arrangement could enable a ‘federation’ of transport associations in the North of England. There might be one transport association around each of Liverpool, Manchester, Sheffield and Hull, plus one for West Yorkshire. Each transport association is responsible for co-ordinating public transport in its area of responsibility, and has its own internal fare policy, but the fares for travel between the transport associations are integrated.

The natural next step, of course, could be tiling the whole of Great Britain with a mosaic of transport associations. I am not sure what the answer is; there are good arguments for treating long-distance fares differently from regional and local services. But Verkehrsverbünde at least allow the commuter railway services that account for the vast majority of journeys to have simple, co-ordinated fares.

Transport co-ordination

As well as co-ordinating fares, the Verkehrsverbünde co-ordinate timetables between different transit operators, so that connections between train services and between buses and trains are as quick as possible. This means that timetables are analysed according to the time taken for whole trips, rather than individual segments.

I have previously written about how Switzerland co-ordinates timetables. The Swiss method involves having all long-distance trains calling at interchange stations around either xx.00 or xx.30. Although the method is effective, it has the obvious downside of requiring big interchange stations with lots of platforms, so that all trains can be in the station at the same time.

Nevertheless, the principle of timetable co-ordination is still sound. The point is not to make sure that every connection works, which is impossible, but to optimise as many connections as possible. The elaborate Swiss system is one way of accomplishing this, but you can get far by simply means lining up schedules so that, for instance, a local bus arrives at xx.17 in time for a local train to the city centre at xx.20.

Timetable co-ordination works. When the Tyne and Wear Metro first opened, its services were co-ordinated with buses. As well as integrated tickets, the timetables were co-ordinated, so that buses would be scheduled to arrive a few minutes before a Metro train departed. Some stations like Four Lane Ends and Regent Centre were rebuilt to act as bus/Metro interchanges. In 1985/86, the Metro had 59.1 mn journeys. The next year, buses were privatised and deregulated, which meant the loss of the integrated service, and the Metro recorded 46.4 mn journeys. In 2023/24 it only had 30.7 mn journeys.6

Crucially, in Germany timetables are co-ordinated by the Verkehrsverbünde, but they do not create the timetables. Railway timetabling is very complicated, and there are enormous benefits to making sure that the same organisation owns the tracks and operates the trains.

Britain’s timetable meltdown of May 2018, which led to enormous problems in the North and on Thameslink, is widely considered to have been caused by a splintering train operating companies, Network Rail, and the Department for Transport. To simplify the story considerably, the DfT specified a timetable that was never going to work, and it was left to NR (who own the track) and the TOCs (who operate the trains) to try to implement it, which predictably led to delays and cancellations.

The best way to operate railways is to have one entity that owns the track, operates the trains, and writes the timetables. Infrastructure, rolling stock and operations all need to be co-ordinated to ensure the railway is being run optimally. In the Verkehrsverbund model, transit operators are able to do this; the role of the Verkehrsverbund is to knit these services together into a coherent network, but without trying to specify them down to a minute level of detail.

Furthermore, the Verkehrsverbund focuses on co-ordinating operations and ticketing, not creating infrastructure. When new infrastructure is built, the Verkehrsverbund feeds into the design process, but it does not decide where new stations go or whether a new tunnel gets built. That is the responsibility of transit agencies, with the ultimate decisions being made by politicians.

This ‘light touch’ approach gets the best of both worlds. It avoids the downsides of separate operators being completely independent from one another, with incompatible tickets and duplicated services. At the same time, operational decision-making remains in the hands of the transit operators, and they preserve their independence.

Do they work?

Yes.

A study7 conducted in 1972, seven years after Hamburg’s Verkehrsverbund was created, found that some stations saw passenger increases of 25–110%, and that some journey times were reduced by 25–50%. They also found that bus feeder routes could make operational savings of about 20%, because the co-ordinated timetables allowed them to be rationalised.

The Verkehrsverbünde have also been successful in increasing passenger usage.

(These data come with some caveats: they’re adjusted for neither population growth nor exogenous economic factors, and nor do they take into account new infrastructure. Data from before 1990 from here,8 and from 1990 to 2015 from here;9 I have been unable to find more recent figures.)

Just as importantly, Germany’s Verkehrsverbünde have been successful at increasing the proportion of operating costs covered by fares.10 In 1990, transport operators within Munich’s Verkehrsverbund covered 58% of their costs from fares; by 2016 this had risen to 80%, with operations within Munich itself covering all their costs. Similar figures were reported for Hamburg; both networks are tightly focused on a single city region, and unlike those of Berlin and Vienna do not include swathes of countryside where services are difficult to operate profitably.

Because they only co-ordinate fares, the economics of Verkehrsverbünde are reflective of the economics of public transport more generally. Any opex deficit needs to be covered by public subsidy, but it is a political choice as to how much subsidy should be given out (and therefore, how high the fares should be). It is also a political choice as to whether a profitable transit network in a central city should cross-subsidise unprofitable rural services. The Verkehrsverbund model is agnostic: it can work with high subsidy or low subsidy.

Should Britain adopt this model?

One of the reasons why nothing works in Britain is that politicians cannot easily make decisions for which they can be held accountable.

Elected leaders come to power, having made promises to the electorate – and then discover that there are precious few levers that they can pull to fulfil those promises, and those that they can pull are not attached to anything. Policy becomes bogged down in a morass of committees, consultations, steering groups which all fall under the heading of ‘engagement with stakeholders’ (a polite euphemism for ‘vested interests’). A sensible degree of consultation with those affected by the decision gives way to sluggishness, even if the stakeholders all agree; if the policy is opposed, then its implementation becomes harder still.

Stakeholderism has a pulverising, macadamising effect on politics. Elected leaders become impotent to enact change, let alone enact it quickly. The public come to distrust their leaders; the leaders come to be frustrated with the system.

Conversely, clear lines of accountability can enable better governance. The Madrid Metro was able to expand quickly and cheaply in no small part because in the Madrileño elections the two main political parties competed with one another to promise who would deliver the most new metro lines – and then had to make sure that they actually delivered it. It is also more democratic. Voters know exactly whom to blame if things go wrong, and whom to thank if things go right. And it is common-sensical. If everybody is responsible then nobody is responsible, and getting things done is harder.

My concern with the Verkehrsverbund concept is that lines of accountability are unclear. Suppose we import the following model from Germany to Manchester.

The North West Transport Association covers Greater Manchester, and also the bits of Cheshire, Derbyshire and Lancashire that are part of its metropolitan region. It has the same responsibilities as a German Verkehrsverbund: co-ordinating timetables and fares, but not operating anything itself. The zonal fare system can grow naturally out of the one currently being developed by Transport for Greater Manchester.

Infrastructure remains the responsibility of elected politicians. Andy Burnham is given the ability to fund transport infrastructure locally, like mayors can in France. A Manchester Metro might be operated by TfGM; a network of suburban trains focused around Manchester (but running out as far as Preston and Crewe) might be operated by an arm of Great British Railways; the Mayor of Lancashire might be responsible for funding a tram system in Preston; Blackpool Borough Council would continue to run the trams there.

My concern is that it is unclear who would be ultimately accountable for the performance of the North West Transport Association. The German model is an association of local governments; in other words, a QUANGO. Even though the major city tends to be the dominant player, there is no single person who is accountable for its performance.

I think this concern should be taken seriously, but it is not a reason to reject the model entirely. It is important to remember that a transport association merely co-ordinates fares and services, and passengers have no interactions with it directly. The things passengers tend to complain about would not fall into its ambit. Delays and crowding would remain the responsibility of transport operators. Infrastructure and the level of fares would still be determined by how much money politicians are willing to spend on public transport. Transport associations will not in themselves diminish the accountability of the railway network to elected leaders.

In Britain, we often think that full nationalisation under a single body is the only way to have co-ordinated public transport. This was the impetus behind the establishment of the London Passenger Transport Board in 1933, which owned and operated nearly all local public transport in and around London. A similar model was used for some of the Passenger Transport Executives established after 1968. In both cases, railway services that were not part of the LPTB or the PTE were not included in their unified fare system.

This owes much to tacit assumption that the operator is the same as the public transport network. This assumption is wrong. There should be a single public transport network for the North West. But trams in Blackpool, buses in Wigan, a future metro in Manchester and suburban trains across the North West are operationally very different, and should not be run by a single monolithic organisation.

Indeed, a monolith is less answerable to the people it serves: if there is a localised problem with the trams in Blackpool, then it is easier to blame an operator based in Blackpool and owned by Blackpool Council, than one based in Manchester whose area of operations stretches as far south as Crewe. Transport associations, in other words, enable greater accountability, rather than hindering it.

I also think the risk of transport associations’ failure can be overstated. In AI safety, the word ‘alignment’ is used to mean an AI system that advances our goals and preferences. To borrow that term and apply it to government, I think that it is relatively easy to create transport associations that are well-aligned. Co-ordination of timetables is the kind of exercise that lends itself well to evaluation by objective metrics, and co-ordination of fares into a zonal system is hard to do badly. Transport associations are responsible for a very circumscribed aspect of the public transport system, which has few interactions with other parts. I think the risk of their failure is low.

And finally, we should not forget about the great benefits to passengers from simple fares and co-ordinated timetables across a metropolitan region. There is no perfect way to achieve this: the world is second best, at best. But transport associations seem to come close to being the best we have so far found.

Transport associations for Britain

Here, then, is a sketch of a model of transport associations in Britain.

First, they ought to be set up around all of our city regions, and should cover the whole of the region.11 I am (at the moment) agnostic as to whether they should also include big rural areas outside of the city region like in Berlin.12 In principle, there is no reason why they could not be set up in rural areas as well.

Second, they should be associations owned by metro mayors and local governments, and should be able to co-ordinate all public transport, irrespective of who owns or operates it.

Third, some sort of special arrangement needs to be made for the South East. I would suggest that transport associations centred around Brighton, Reading, Cambridge etc be federated into an association that co-ordinates fares across the South East.13 This prevents one giant body co-ordinating buses and trains from Margate to Newbury, while also ensuring simple fares across the region. Likewise, there would be a federation of transport associations in the North.

Fourth, there must separately be reforms (probably as part of Great British Railways) to ensure that track, train and operations on mainline railways are united under the same body. This is not directly related to the transport association model, but is clearly part of the bigger picture.

Fifth, as another separate reform, metro mayors should be able to decide on what infrastructure to build, fund it locally, and take political responsibility for its construction and subsequent operation.

What transport associations offer is the best of both worlds: decentralisation of operations and funding decisions, while ensuring that this decentralised system is co-ordinated into one network. Do this, and we will be able to have the best public transport network in the world.

Ralph Buehler and others, ‘Verkehrsverbund: The evolution and spread of fully integrated regional public transport in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland’ (2018) 13(1) International Journal of Sustainable Transportation 36, table 3.

TfGM is in the process of integrating fares – including rail, bus and tram – across its area of responsibility. Furthermore, the English Devolution White Paper suggests that the Mayor of Greater Manchester (and presumably by extension TfGM) will have a ‘statutory role … in governing, managing, planning, and developing the rail network’ and a ‘right to request further rail devolution, up to full devolution of defined local services’.

This has been complicated by the introduction of the Deutschlandticket, which for €58 a month enables unlimited travel on all public transport throughout Germany, except for long-distance trains. As a result, HVV offers fewer monthly tickets.

A similar system was used on the Tyne and Wear Metro in the 1980s; see S Davoudi and others, The longer term effects of the Tyne and Wear Metro (Transport Research Laboratory 1993), 12.

I would suggest zones for: Leeds; Bradford; Huddersfield; Wakefield; York; Halifax and Calderdale; Airedale and Wharfedale; Holme and Colne Valleys; the ‘five towns’ area; Selby; Dewsbury and the Spen Valley; and the area comprising Harrogate, Wetherby and Tadcaster.

Figures from the Department for Transport.

Wolfgang Homburger and Vukan Vuchic, ‘Transit Federation – A Solution for Service Integration’ (1972) 2 UITP Revue 84.

John Pucher and Stefan Kurth, ‘Verkehrsverbund: the success of regional public transport in Germany, Austria and Switzerland’ (1995) 2(4) Transport Policy 279, table 2.

Buehler and others (n 1), table 4.

Figures from Buehler and others (n 1), table 7.

They should hew to local government boundaries if possible, but I see nothing wrong with cutting a district in half if its boundaries are badly drawn. For instance, the northern half of High Peak is within Manchester’s orbit, while the southern half looks to Derby.

It is worth noting, however, that even a ‘maximalist’ definition of a transport association is not very big. The entirety of the West Midlands region, which stretches from Stoke down to Herefordshire, is more similar in size to the areas covered by the Munich or Hamburg Verkehrsverbünde than Berlin’s behemoth.

I am not sure how this would work with Oyster cards, given that the Oyster system can only support up to 16 fare zones. This seems like the sort of problem that is readily surmountable.

Where i live we have a system that works similarly to this.

The cities and towns are each independent zones, where you can transfer between services within them without extra cost (within a time limit). Between them the fare is calculated based on distance (essentially treating them as points).

Instead of having seasonal or monthly tickets, most people pay with an app that calculates your monthly fares which are capped at the price of the monthly ticket (so you don't need to plan in advance).