Britain is in the midst of an awakening. The stagnation that has afflicted the country for the past decade and a half is being recognised for what it is – our national ruin. New groups seem to spring up every month, giving voice to those who reject decline and embrace growth, abundance and progress. The vibe has definitively shifted.

When it comes to transport policy, the Abundance movement has coalesced around a few ideas that it would be best to call political memes. They are not sufficiently thought-through to be called policies: they are reflections of ‘this is a good idea’. One of those political memes is that we should build trams everywhere.

I think this has been seized upon for two reasons. The history of trams in Britain fits neatly into the narrative of the Abundance movement. Built in the nineteenth century by private enterprise, every city ended up covered in a thick web of tram tracks. You could just do things back then. And then, unlike some foreign cities (and Blackpool) which kept their Victorian tram systems, we foolishly dismantled them in the 1950s to make room for cars. Belatedly we realised in the late 1980s that this was an enormous mistake, but our inability to build meant that only a handful of cities received tram networks. In 2000, the government spoke optimistically about building 25 new tram lines by 2010; none were built, due to high costs. We build trams more expensively than nearly any other country. As a result, Leeds is the largest city in western Europe (defined by its political boundaries) without any sort of tram, metro or light rail system.

The story of trams is a story of entrepreneurial material progress giving way to stagnation and an inability to Get Things Done; it fits perfectly with the wider story we wish to tell about Britain.

Trams also play into another goal of the Abundance movement: good urbanism. AI-generated images of beautiful streets built at gentle densities are rarely complete without a tram running down the road.

Trams are as much a part of the aesthetics of Abundance as they are an instrument of transport policy. It helps that they are, unlike metros, visible at street level. In part this is just a question of urbanism: the ubiquitous tram makes it clear that a good city is one that puts cars in their place, as well as one that is built beautifully. Anybody who has been to Amsterdam or Vienna knows that trams can enable good urbanism.

But trams are aesthetic in a deeper sense. Their history means they are intimately connected with the triumphant past of our great cities. By restoring trams, we are restoring a certain idea of Britain: the Britain that was at the forefront of the world’s industrial progress, whose national aesthetic was inclined towards plenty. It is the opposite of today’s lugubrious, dismal Britain.

I do not think that the Abundance historiography is wrong, and nor do I disagree with the underlying aesthetics. But trams are often not the right solution for our cities. They are slow, and as I have previously written, this means they are often unsuitable for bigger cities like Leeds, which should instead use a tram-metro.

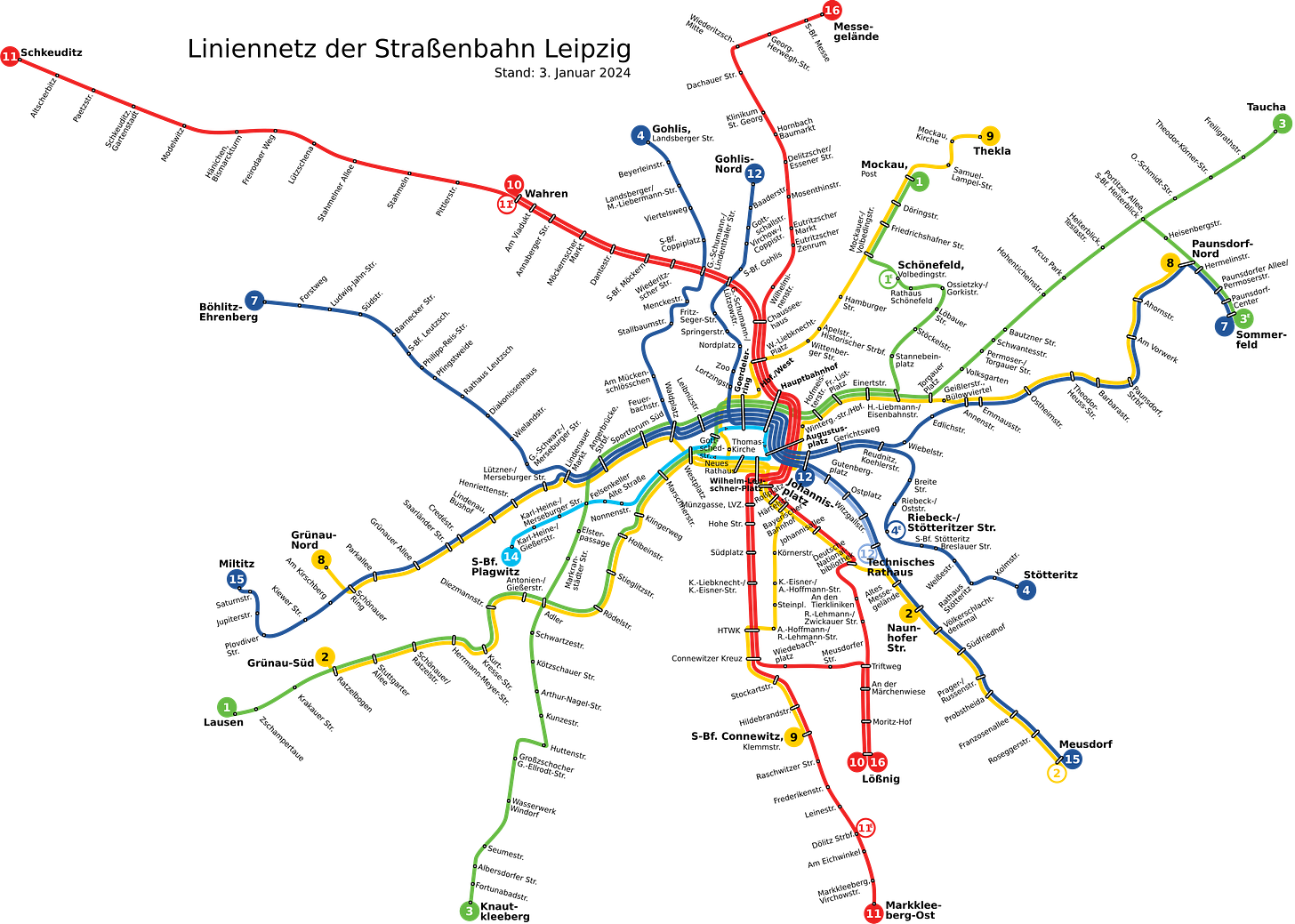

If we compare Britain’s biggest cities outside of London with similar-sized ones in Germany, the pattern becomes clear. (For the definitions I am using, see this pedantic footnote.1)

With a few exceptions,2 German cities with more than a million people have a full metro. They might also have kept some trams, but the city is not reliant on the tram network. Those with between half a million and a million almost always have a tram-metro. Those with fewer than a million rely only on a tram system. This should in itself give us pause for thought when we think about building trams in our great cities outside of London.

Where do trams work?

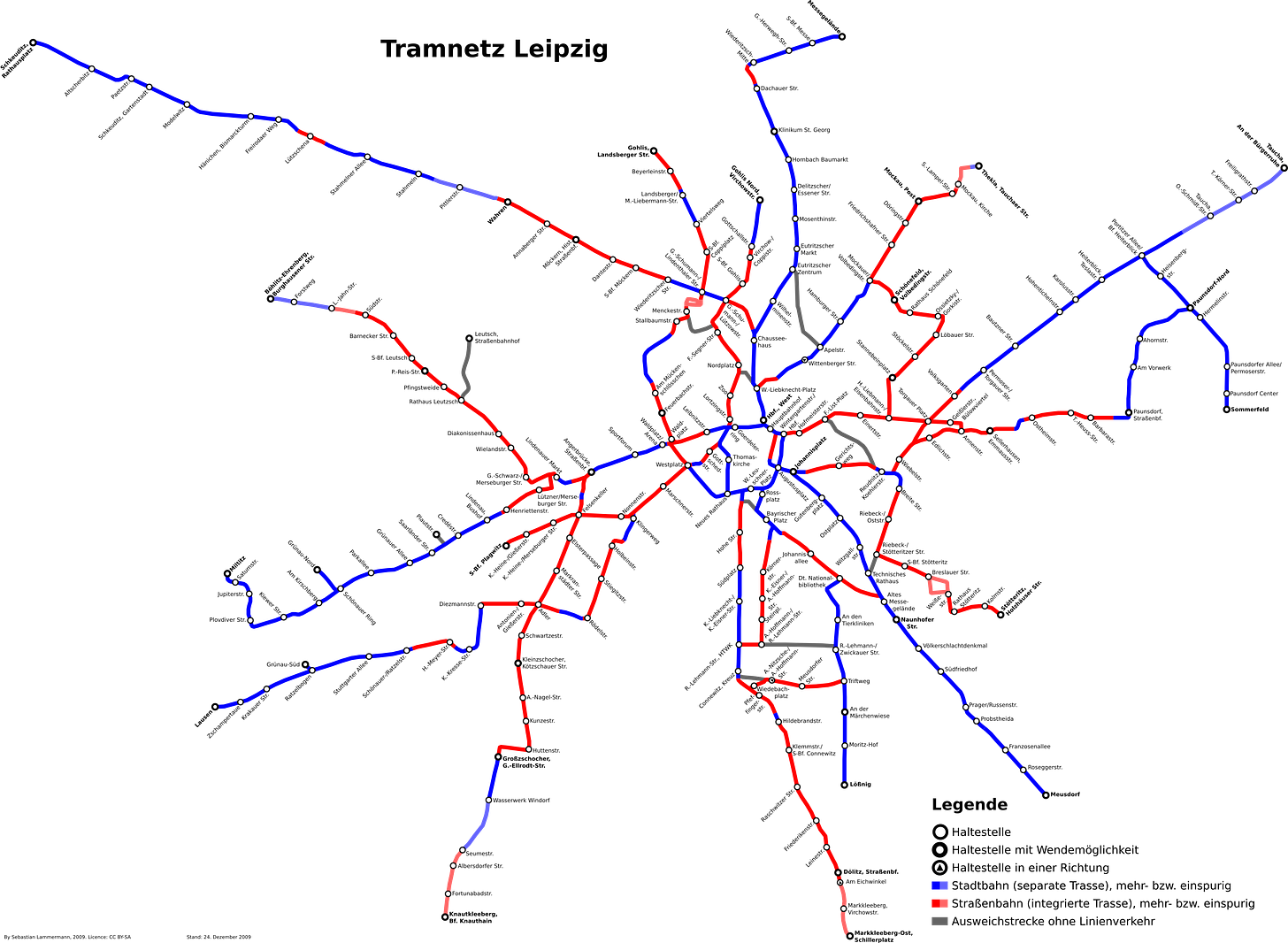

Leipzig is one of those exceptions, because it was in East Germany: while West German cities put their trams underground in the centre (partly to make room for cars in the city centre), East German cities did not. Given Leipzig’s size, it is likely it would have built a tram-metro were it not for the Iron Curtain.

Leipzig is therefore the biggest Germany city dependent on trams, so can help us understand why and where they work.

In its suburbs, Leipzig has a large number of wide arterial roads arranged in a distorted grid pattern. In many cases, the roads are wide enough that trams can have their own lane. Where they do share space with cars, the grid system means that the shared roads often have the character of local roads, so are not especially busy.

Crucially, the trams do not run on the narrow streets in the historic centre of Leipzig. Like many continental-European cities, Leipzig has a wide ring road built on the site of its historic city walls, and the trams run along this road.

As anybody who has used Sheffield’s tram system can attest to, a tram system running on narrow arterial roads and along wiggly city-centre streets is likely to be slow. In an ideal world Leipzig would probably have a tram-metro, but it can get by with a tram system because its street layout enable the trams to be as segregated as possible from other traffic.

These conditions are rare in British cities. Take Bristol. Bristol’s street layout is a jumble, probably more than any other large British city. It has no wide arterial roads in the suburbs, and finding a sensible route through the old winding streets in the city centre would be a nightmare.

In fact, the same urbanism that makes a tram system slow in Bristol would make a tram-metro slow as well: Leeds is well-suited to a tram-metro because it has many wide suburban roads on which trams can easily be run. In Bristol, I worry that a tram or tram-metro would be severely compromised, as is the case in Sheffield.

Focusing on the political meme of trams ignores the reasons why they work. Trams work either where a city is either small enough that slow journeys (compared with a metro or tram-metro) are unproblematic, or where it has enough wide arterial roads that the trams can be mainly segregated from other traffic in the suburbs and there is a sensible route through the city centre. Tram-metros are useful in places like Leeds where a tram system would work (because of the wide arterial roads), but for the fact that crossing the city centre is a barrier to quick journeys.

Suburban rail: the opportunity for Britain

Furthermore, I think that trams are the wrong focal point for the Abundance movement. Something that goes under-discussed is that (with a few exceptions)3 British cities have the densest suburban railway networks on the planet.

Within 20 km of Manchester city centre, there are 20 suburban railway lines. Kyoto, which has a similar population, has 11.

Glasgow has 22 lines within the same radius, and the same population as Zürich, which has 16.

Even Leeds, which has 700,000 fewer people than Kyoto within that radius, has 12 railway lines.

I have chosen these comparisons deliberately because Japan and Switzerland are widely regarded as having the best railway networks in the world. Our cities of course do not. The systems around Leeds and Manchester are predominantly unelectrified, infrequent, slow and unreliable. Glasgow’s network is better, but even then the quality of service is not uniform.

But there is an enormous opportunity here. We could, if we upgraded our suburban rail, have even better networks than either of those two countries. By doing what the Swiss and Japanese have done, we could have suburban networks that are fast, frequent, reliable and cover the city even more comprehensively than in those two countries.

We need to turn the policy meme of ‘trams everywhere’ into actual policy ideas for what to build in Britain’s cities (and, just as importantly, how we set up the institutions to enable building these things). For instance, I think:

We should upgrade Manchester’s suburban railway network, and build a few metro lines to fill in the gaps.

We should upgrade Leeds’ suburban railway network, and take advantage of the wide arterial roads to give the city a tram-metro.

Bristol, unusually, has almost no suburban rail. Its difficult street layout, size, density and affluence means that it can probably justify a metro system like Nuremberg’s, which uses short trains to keep the costs of building stations low.

Trams, meanwhile, should be confined to smaller cities like York (200,000 within 10 km) or Oxford (260,000) or Derby (330,000) or Stoke (400,000) or maybe Southampton (510,000), which are small enough that the long journey times are less problematic.

For Leeds and Bristol and Manchester, we should be aiming higher. The advantage of being a developing country is that we don’t have to be the trailblazers: we can learn from other countries that have had to solve similar problems. We can plunder the rest of the world for ideas about how to do things better.

The scale of the opportunity presented by our legacy railway networks is immense. Rather than AI-generated images of pretty trams, the foundational meme of transport policy for the Abundance movement should be that Manchester could quite easily have the best railway network of any medium-sized city in the world. That would be abundance.

To enable comparison with German systems, I am using the term ‘metro’ to refer to a system that is fully grade-separated and which consists wholly or predominantly of newly-built infrastructure, such as the Glasgow Subway or Munich U-Bahn. The Tyne & Wear Metro is not by this definition a metro, because it took over pre-existing suburban lines which run through the city centre in tunnels. Likewise, the Frankfurt U-Bahn is not a metro, because it is a tram-metro system.

The term ‘suburban railway network’ refers to the practice of running suburban lines through the city centre (usually in a tunnel) rather than terminating at a central station. In Britain, this describes the Tyne & Wear Metro, Merseyrail and the Argyle and North Clyde Lines in Glasgow; in Germany, it describes the S-Bahn systems.

Apart from the exceptions in the table, Cologne has a tram-metro even though it has more than a million people (and Frankfurt is not far off).

The exceptions are Bristol and Nottingham, and to some extent Sheffield.

Really good read, a few thoughts/ questions.

Leeds - seems very poorly served by the suburban rail lines that exist there and lack of stations on them as well as poor frequency. Feel a relatively cheap and fast way to improve connectivity there alongside a Nuremburg style tram-metro

Bristol - Likewise not amazing suburban service on the lines that do exist although slowly improving. Have you written/ read much on a metro system or concepts to improve the local trains?

Trams in smaller cities - do you think they should be prioritised in already prosperous/touristy places like Bath/ York, or as a stimulus in less well off places?

What would you suggest for BCP (Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole), which is small ish 400k but extends to 580k with immediate hinterland, has a single suburban railway and used to have trams but now just buses and cars?