The Chelsea–Hackney Tube Line

A new Tube line to fill in the gaps in the London Underground network

I have previously written about how to build Crossrail 2 more cheaply. The short version is: by intelligently re-using current and abandoned bits of track, we only have to build three expensive underground stations and 13.5 km of tunnels, to get similar benefits. This compares with 11 or 12 new stations and 35 km of tunnels in the current plans.

There is an obvious problem with this approach. My route descopes Crossrail 2, so it is solving fewer problems. This means it offers no relief for the southern bit of the Northern Line, no new transport links for Chelsea or Hackney, and indeed very few new links at all: most of my route duplicates existing lines.

I think this is justified. A single transport project cannot and should not try to solve every problem at once. Britain has what I call ‘once-in-a-generation syndrome’: we (rightly) believe that a project is going to be our only megaproject for decades, so it has to take on the role of fixing every problem. This leads to projects that try to solve too many problems and succeed at solving none of them.

Once-in-a-generation syndrome also inflates costs. While the benefits of a project should rise with the costs, it is safe to say that the Treasury and sceptical ministers care more about costs of a project than its benefits.

Adding bells and whistles therefore makes it less likely the project gets built at all. Such is the urgency of the need to relieve the Victoria Line that I would much rather have a slimmed-down Crossrail 2, maybe even an imperfect Crossrail 2, over no Crossrail 2 at all.

Nevertheless, something does need to be done to fix the transport problems that I leave out of the scope of Crossrail 2. Hence, I have got my crayons out to propose this line, the Chelsea–Hackney Line.

When I show this map to people, their first response is often, ‘it’s so wiggly!’ That is true, but wiggles are not bad in and of themselves. Instead, the route is driven by the problems that the line is trying to solve, which I discuss in this article.

(The wiggles might be bad if they slowed the line down, but I estimate it will take about 11 minutes to cross the centre from Old Street to Victoria, so it is safe to say the slightly indirect route does not have an enormous effect on journey times.)

The next article in the series will go through the route in detail. In short, the line takes over the Chingford branch of the Overground, and the slow lines of the Brighton Main Line between Clapham Junction and Selhurst, before heading to Croydon. They are linked by a tunnel that serves Chelsea and Hackney, and also areas of central London that are poorly-connected.

To be clear, I think that the Chelsea–Hackney line is something that we should build after Crossrail 2, and after other projects like the Bakerloo Line Extension. This is because our construction costs are currently so high that this line does not have a chance of getting past the Treasury.

We first need to learn how to get our costs down from $889 mn/km of tunnel for Crossrail (under central London and with big stations) or $551 mn/km for the Northern Line Extension (which has no such excuses: it was built under brownfield land, and with smaller stations). I would suggest a target of $200 mn/km for the newly-built parts of the line, which is in the range of Nordic costs, and roughly double Spanish costs.

We are not going to achieve this overnight: we will first need to learn how to build infrastructure properly. I expect that Crossrail 2 and the Bakerloo Line Extension will be expensive, but hopefully projects built after that will be cheaper. At $200 mn/km the line, which has 21.5 km of tunnel (about the same amount of tunnelling as Crossrail), should cost in the region of £4–4.5 bn.

Problem 1: ‘Tube deserts’ in Zones 1 and 2

The Chelsea–Hackney line has a long history: it started out as a proposal in the 1970s for a Tube line, before morphing into Crossrail 2. Throughout all the changes to its route and scope, however, one thing has been constant: connecting Chelsea and Hackney.

This is because Chelsea and Hackney really are ‘Tube deserts’. The only tube station in the entire Borough of Hackney is Manor House, which only serves to emphasise the problem: even though the platforms are in Haringey, the entrances are in Hackney because the border goes down the middle of a road.

Hackney is dependent on buses and the Overground for transport. Neither is up to the standard of a rapid transit network in a megacity like London. Buses are slow and unreliable. The ‘Weaver Line’ is insufficiently frequent and doesn’t go through the centre. (It terminates at Liverpool Street.) The ‘Windrush Line’ is very useful for circumferential journeys, but is a poor substitute for a Tube line that takes people quickly into the heart of the city.

Chelsea fares a little better, because Sloane Square serves the northern half of King’s Road, and some of Chelsea is within the catchment area of South Kensington. But the heart of Chelsea, the area around the fire station, is a kilometre from either station, which is not really acceptable for such an important Zone 1 sub-centre of London.

There is, in fact, a third Tube desert which receives less attention: Battersea, which is dependent for its rail links on Clapham Junction, at the southern tip of the district.

The Chelsea–Hackney line plugs these gaps, with a station in Chelsea, one in Battersea and four in the London Borough of Hackney. As discussed below, it will also enable a better service to the bits of Hackney not served by the line, by freeing up space in Liverpool Street for more Overground services.

Problem 2: Access to ‘Midtown’

London has two major central business districts: the City and the West End.

The Tube has evolved so that most Tube stations have fairly easy access to both the City and the West End. This is straightforward on lines that run east–west, like the Central Line, which goes into the heart of both centres. With north–south lines, direct access is harder, because a trunk line cannot serve both the City and the West End at the same time. Nevertheless, the network of interchange stations means most places have a satisfactory connection to both centres.

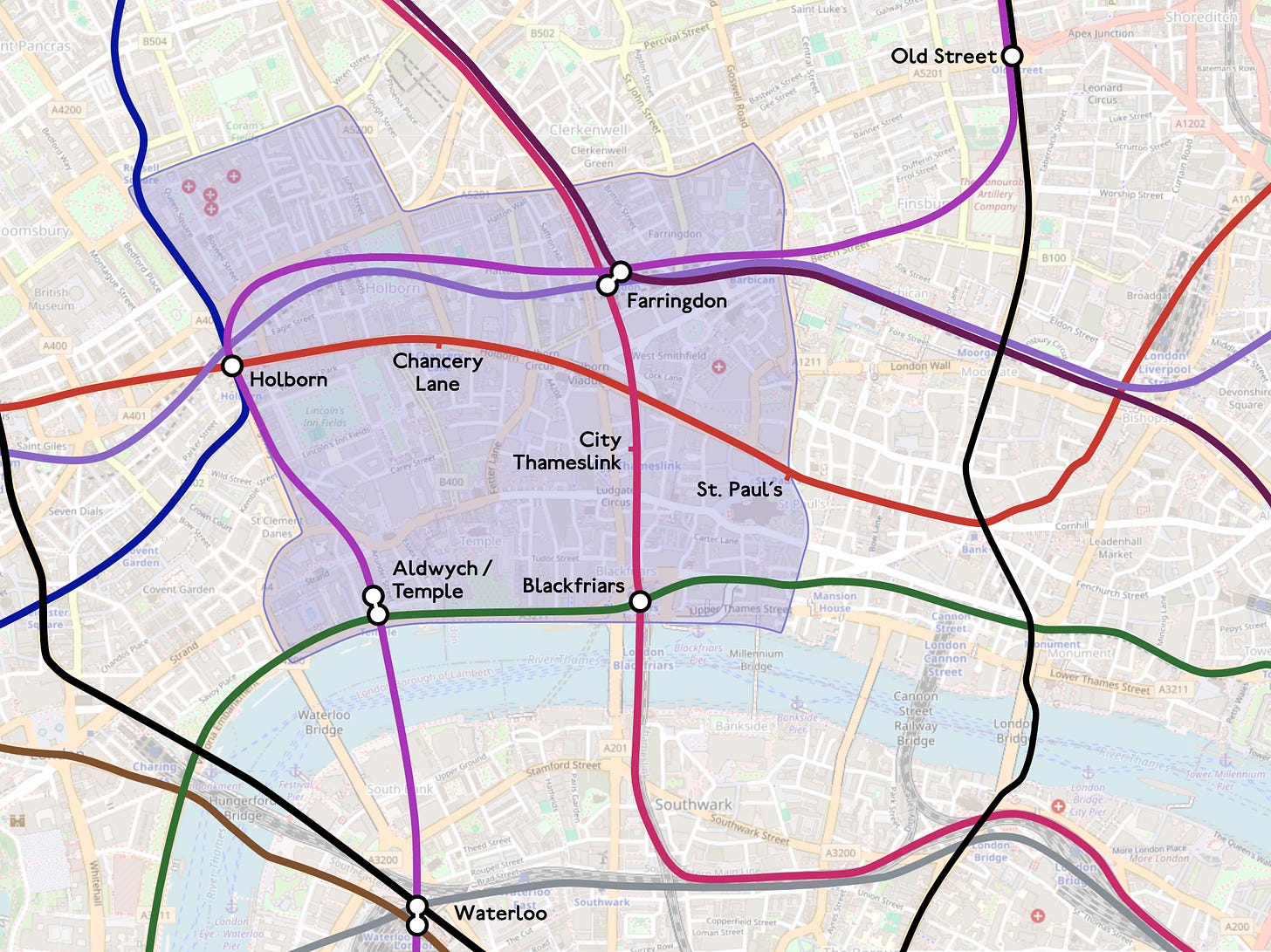

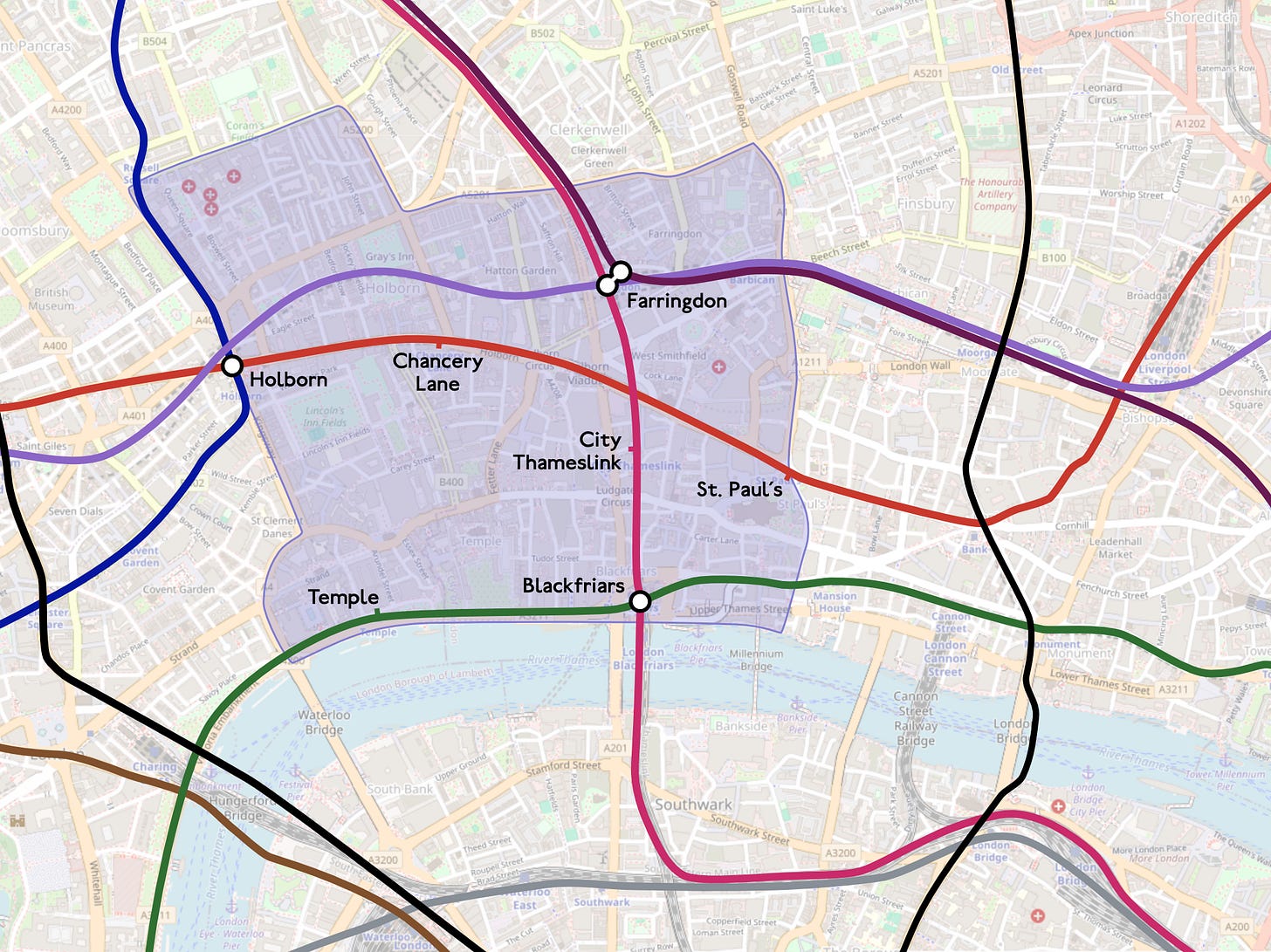

But really, London has a third business district in the centre. Between the City and the West End is an area that has no fixed name, although about five years ago some estate agents tried to brand it ‘Midtown’, an execrable Americanism that nevertheless is the best anybody has come up with so far. Very roughly, it is this area:

‘Midtown’ is of course well-known as the centre of London’s legal profession, but it’s not just lawyers: there are also financial and other professional services, and various bits of the colleges of the University of London.

As a result, ‘Midtown’ has surprisingly high employment density. In 2013, the latest year for which figures are available,1 there were 114,000 jobs in the Holborn and Covent Garden ward of Camden, which encompasses about half of Midtown. The other half is in the City, for which breakdowns by ward are not available, but if we assume that a quarter of the City’s 392,400 jobs are in ‘Midtown’, then we can say there were about 200,000 jobs in ‘Midtown’ in 2013. This compares with 217,900 for the West End ward of Westminster.

In spite of its employment density, ‘Midtown’ can be quite hard to get to. As the map shows, it has quite a few stations, but except for Farringdon, City Thameslink and Chancery Lane, they are all on its edges.

Thanks to the Elizabeth Line station at Farringdon, ‘Midtown’ is much better connected than it was. But it is still quite hard to get to: of London’s major mainline termini,2 Euston and Waterloo do not have a direct service, while Victoria only has the District Line which runs along the edge of ‘Midtown’.

The Chelsea–Hackney Line is like the Victoria Line for ‘Midtown’. One of the main purposes of the Victoria Line was to connect Victoria Station to the West End. Before the Victoria Line opened, Victoria Station was only served by the District and Circle Lines. Getting to Oxford Circus meant changing at Embankment; getting to Green Park required two changes of train. This changed with the Victoria Line, whose main purpose was to improve access to the West End.

The central core of the Chelsea–Hackney goes Victoria – Millbank – Waterloo – Aldwych – Holborn – Farringdon – Old Street. This will connect both of the southern termini to the heart of ‘Midtown’.

It will also cater for some other journeys that are currently quite fiddly. Most notably, Victoria and Waterloo will have a direct link, and both will be connected with the tech cluster around Old Street. Millbank station serves an area with a high density of government offices that can be quite hard to get to. All of these places will also be connected to Farringdon, which has become one of London’s most important stations ever since the Elizabeth Line opened.

Problem 3: The Lea Valley Lines

.A common problem with Britain’s railways is too many branch lines funnelling into the same trunk. This means each branch is competing with the others for space on the trunk, and the railway has to make an ugly trade-off between running the branches at an appropriate frequency, and ensuring that delays do not cascade to other services that use the same trunk.

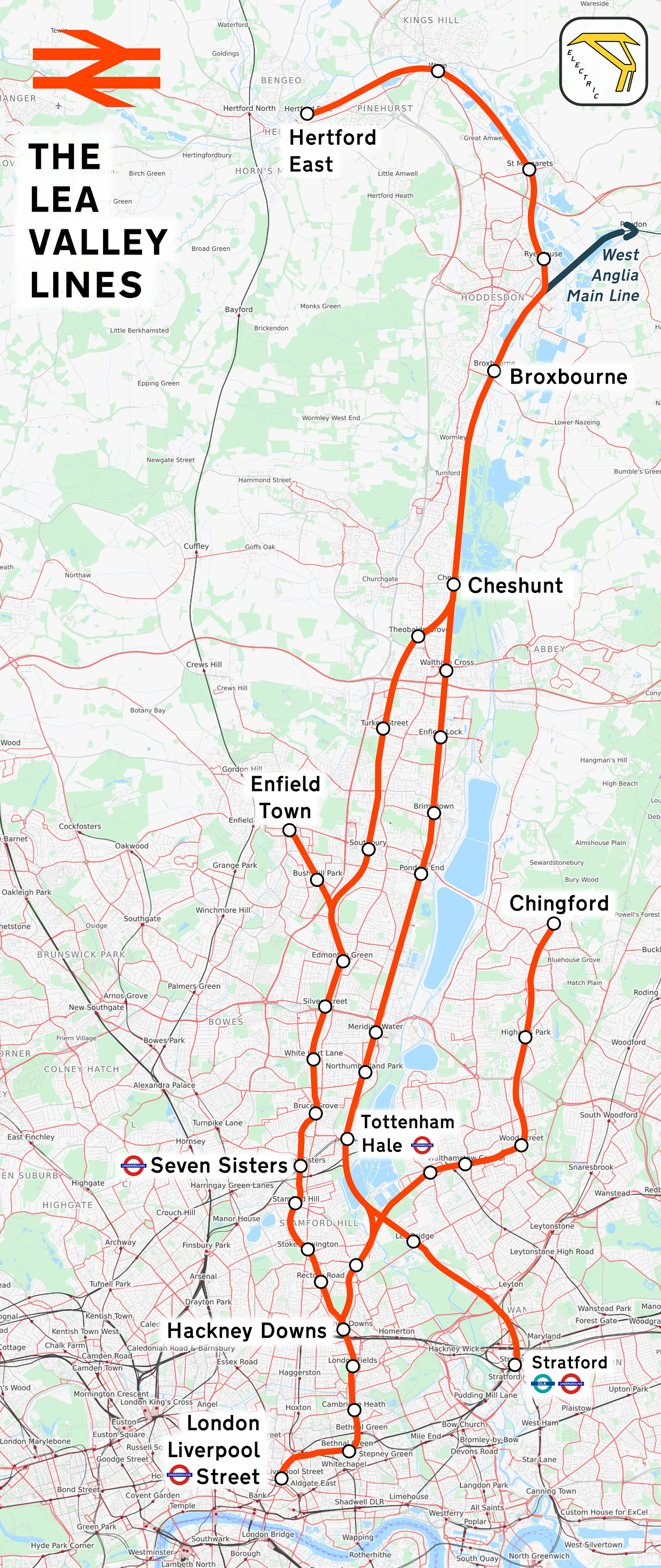

This is certainly true on the West Anglia Mainline (WAML). The WAML runs from Liverpool Street to Cambridge,3 with a branch to Stansted Airport. It also has a complex network of branches within London known as the Lea Valley Lines.

At the moment, during the morning peak 18 trains per hour (tph) arrive from the WAML and its branches at Liverpool Street.

Of those, 8 tph come from the Overground branches from Enfield/Cheshunt and Chingford, 4 tph each. This is not good enough. Both of them run through dense London suburbia. At the barest of minimums, they should each get a train every ten minutes. Ideally, they should have a train at least every five minutes or better, which is what branch lines on the Tube usually receive.

The remaining 10 tph come from the WAML itself, from north London, Hertfordshire, Stansted Airport and Cambridge. At the moment, the WAML itself is not one of London’s busier lines. But that is likely to change. Within London, the WAML is a major opportunity area: 21,000 homes could be built near the line on the site of industrial estates and ‘boxland’ retail. Outside of London, there are plenty of opportunities for green belt development along the route of the line.

The current aggregate frequency of 18 tph on the WAML and its branches is therefore inadequate, and is only going to become more so. (Even with signalling improvements, 18 tph is probably the limit of what can be operated reliably, given the complexity of the branches and mixture of fast and stopping services.)

Crossrail 2 will remove the stopping services from the WAML. This will help, but won’t be enough in itself – it will enable at the most 2 tph more on the Overground compared with today’s service patterns.

The Chelsea–Hackney Line will remove the Chingford branch, and run it directly into the centre of London. Together with Crossrail 2, this will reduce the frequency into Liverpool Street to 12 tph; the spare train paths can be used to improve the frequency on the Enfield/Cheshunt branch, and maybe also improve the service to towns in Hertfordshire.

(This isn’t the only thing that should be done to improve the WAML – but that will be a matter for a future post.)

Problem 4: The Northern Line

The most overcrowded part of the Tube is the southern bit of the Northern Line, between Stockwell and Morden.

There are two reasons for this. One is that the Northern Line only runs 24 tph off-peak, and 28 tph in the peak. This is because the Northern Line reverse-branches: the two northern branches, to High Barnet and Edgware, each get direct services to both Charing Cross and Bank. If you get on a train at High Barnet, the trains alternate between the Bank branch and the Charing Cross branch, and at Edgware, they do the same.

According to TfL, the frequency problem can only be fixed by splitting the Northern Line.4 TfL want to pair one of the northern branches with the Charing Cross branch, and the other with the Bank branch, with both branches having a service of at least 30 tph.

Although this will help, it will be inadequate. The fundamental problem for the Northern Line is that it is the only good rapid-transit service in a swathe of southern London.

To relieve the Northern Line properly, the lines running nearby need to be upgraded, so that passengers use them rather than travelling long distances to get to the Northern Line. These lines are:

The South Western Main Line, between Clapham Junction and Wimbledon.

The Brighton Main Line, between Clapham Junction and probably as far as Streatham Common.

The Wimbledon Loop.

The South Western Main Line (the least important) will be upgraded by my proposal for Crossrail 2. The Wimbledon Loop is the most important of these, but it is quite difficult to untangle, and I think other schemes should take care of it.

The Chelsea–Hackney Line’s contribution is in upgrading the Brighton Main Line stopping service between Clapham Junction and East Croydon. This will particularly relieve Balham station, through which both lines pass, as well as the Clapham stations and Tooting Bec.

Obviously, the Chelsea–Hackney Line will not wholly fix the Northern Line. But I don’t think we should be looking for a ‘big bang’ that will completely relieve the Northern Line, or at least, not yet. We should first upgrade the many railway lines that run close to it.

A Tube line, not a Crossrail line

To be clear, I do not think that the Chelsea–Hackney Line will be viable until after we have reduced our construction costs to something similar to Nordic levels.

One way I propose making the line cheaper is by building it as a Tube line, not a Crossrail line. Tube lines are cheaper to build, all else being equal. Best practice for station design is to dig a box as long as the trains and no longer. S8 stock, the type of trains used on the Metropolitan Line, are 133.68 metres long, while the Class 345s used on the Elizabeth Line are 204.73 metres long, 50% longer.

(The tunnels and stations should be built with a big enough structure gauge to operate mainline sized trains like those used on the Metropolitan Line, rather than the smaller trains operated on the deep-level Tube lines.)

Using shorter trains does not necessarily come at a cost of capacity. Because the Chelsea–Hackney Line is self-contained, and has no branches or express services, it will be able to run up to 36 tph, the level of service achieved on the Victoria Line. S8 stock has a capacity of 1,350 passengers: assuming a similar figure, the Chelsea–Hackney Line would have a capacity of 48,600 passengers per hour per direction (pphpd). The Elizabeth Line, by comparison, can ‘only’ cope with 45,000 pphpd, because the branching and signalling limits the frequency to 30 tph.5

Whether this capacity would be used on Day 1 is an open question. On the one hand, the Chelsea–Hackney Line only serves the least important of London’s central business districts. On the other hand, nobody thought the Elizabeth Line or the Northern Line Extension was going to be so busy. There might be an argument for building the line for ten-carriage trains, although this would cause a spectacular increase in costs. Much better, if the line does become overcrowded, to build Crossrail 3 to relieve it.6

To be clear, the Chelsea–Hackney Line is just a proposal. I am sure there are many issues with it that I have not considered (please leave a comment if this is the case). But I don’t think we should be afraid to propose new infrastructure: every Tube line started off as a line on a map. London built six Tube lines between 1890 and 1910. We should be ready to step into the shoes of the Edwardians, and get building again.

I find it shocking that up-to-date versions of these data are not publicly accessible.

These are Paddington, Euston, King’s Cross, St Pancras, Liverpool Street, London Bridge, Waterloo, and Victoria.

Few people travel all the way, as the service from Cambridge to King’s Cross is much faster.

I am slightly sceptical of this claim. Reverse branching (whereby a suburban branch has direct trains to two central trunks, as on the Northern Line) is a bad idea, but the Munich U-Bahn manages to get 2-minute headways, even though it runs two peak time-only reverse-branches. I have not, however, investigated in any detail how Munich does this, and either way, splitting the Northern Line is a good idea.

Currently, the Elizabeth Line only runs 24 tph.

The suburban mainline stations can all (I think) take ten-car trains. But the 16 newly-built stations would all need longer platforms.

Decent read but why isn’t more being done in SE London? Running a tube line out to Lewisham and possibly hayes should be bare minimum. Whole part of the city is deserted. TfL could make a fortune if they built or linked up a new line there.