How Britain became a property-owning democracy

By accident, or by design?

One of the many odd things about Sherlock Holmes is that he has a landlady. Even though Watson says at one point, “his payments were princely. I have no doubt that the house might have been purchased at the price which Holmes paid for his rooms during the years that I was with him,” Holmes stays a renter.

Away from the world of fiction, in all his life John Maynard Keynes never owned a house, in spite of amassing a fortune worth on his death about £20 million in today’s money. Renting, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, was so normal that even wealthy men did it: on the eve of the First World War, only 10–20% of households (sources differ) were owner-occupiers.

Today things are quite different. Not only are 64% of Britons homeowners, but we have a culture of homeownership. We have a national obsession with house prices and the property ladder. Most of the 36% of Britons who are not homeowners would probably like to own a house one day. If they were around today Sherlock Holmes and John Maynard Keynes would definitely be homeowners; an investor like Keynes would probably have a substantial property portfolio.

I am going to use the term ‘property-owning democracy’ to describe this situation.1 The phrase rings deep in British political history, and it refers to much more than widespread homeownership. It is an ideology: mass property ownership will, its proponents claim, make capitalism healthier and more popular. It will give the people a more direct stake in the country’s wealth. Property is more than just an asset, but part of the social contract.

So – between the time of Sherlock Holmes and John Maynard Keynes and the property-owning democracy of today – what changed?

The simple narrative

I think that many people’s mental model of the history of the British housing market looks something like this:

Pre-1945: ???

1945–1979: Post-war consensus, golden age of social housing.

1979–2008: The social contract is reshaped by Margaret Thatcher around individual property ownership. It’s at this point that Britain becomes a nation of homeowners.

2008–present: It becomes increasingly hard for young people to get on the property ladder, the social contract made by Thatcher slowly disintegrates.

In other words, it was all down to Thatcher. This narrative has purchase over both the Left (who think it was a disaster) and by the Right (who think it was a triumph).

This story can be very quickly disproven by looking at this graph.

Clearly, Thatcherism is part of the story, in fact as we shall see a very big part. But seen in a wider perspective, Thatcherism just accelerated a pre-existing trend. Between the Edwardian era and 1979 the homeownership rate went from about 20% (other sources put 10%2) to 57%. The property-owning democracy was on the march well before Margaret Thatcher. Indeed, it was on the march during the postwar period, the ‘golden age of social housing’.

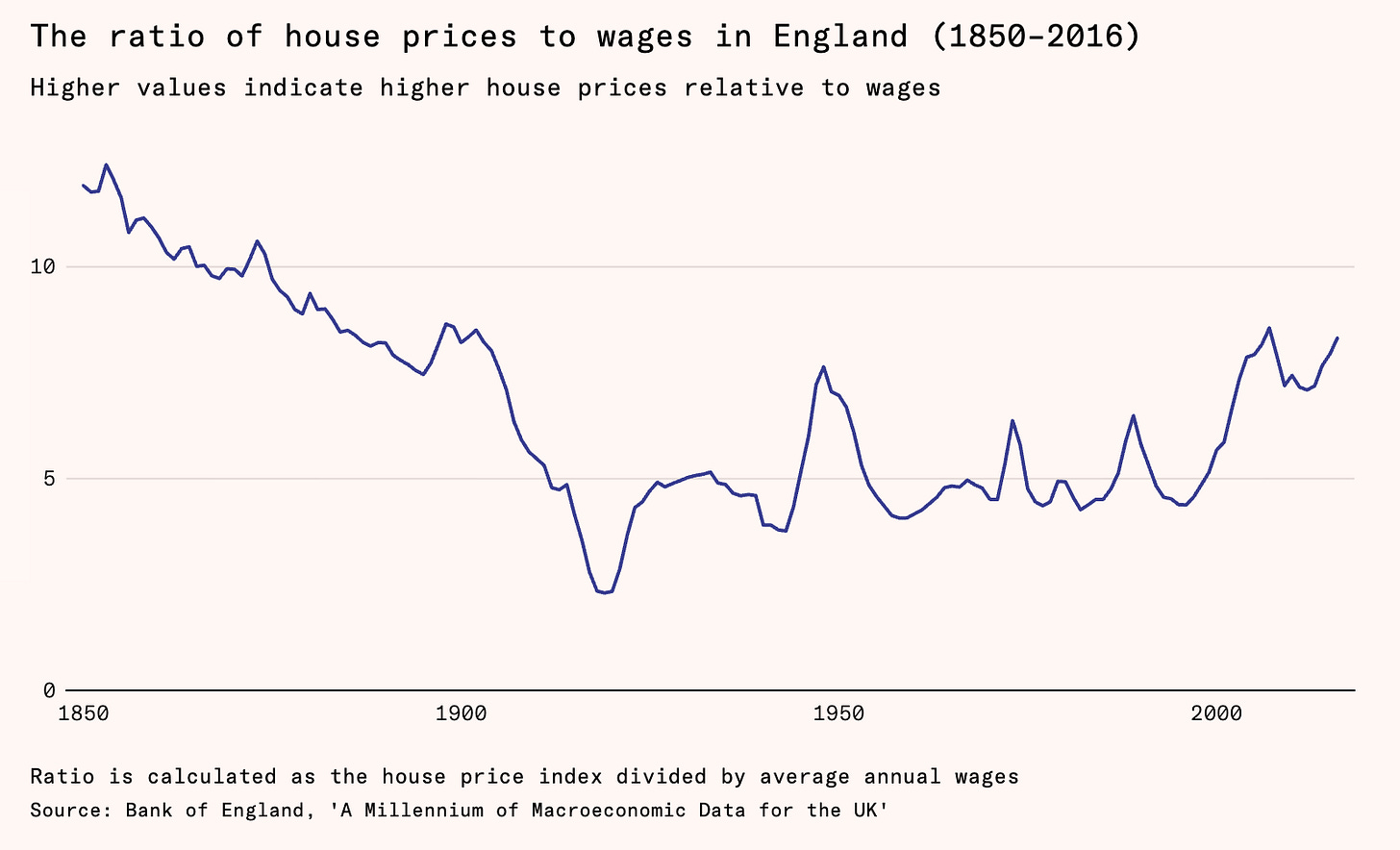

Another simple explanation is that housing gradually became more affordable, relative to wages, over the course of the twentieth century. But this explanation too can be disproven with a single graph:

The story is much more complicated and subtle. It is a mixture of politics and economics. And, as with so many things in Britain, it was often – but not wholly – unplanned.

Theme 1: Tax incentives

In the 1963 Budget, a form of income tax with the glamorous name of Schedule A was abolished by the Conservative government. This is the tax on ‘imputed rents’, the notional benefit that somebody receives from being an owner-occupier rather than a renter.

Suppose you live in and own a property worth £500,000 in London. At a normal London rental yield of just under 5%, that works out to a rental income of £2,000 a month, or £24,000 a year. By virtue of the fact that you own the property you live in, you are saving £24,000 on rent. In other words, owner-occupation gives you a benefit in kind of £24,000 a year.

Normally, HMRC are assiduous about going after benefits in kind: a benefit in kind is usually treated as though it were a benefit in cash. If they didn’t, then employers would pay their employees in perks rather than cash. But when it comes to the benefit in kind that you receive from living in a house you own, the taxman is nowhere to be seen. At the higher rate of income tax, our notional London owner-occupier would have to pay an extra £9,600 to the taxman.

Of course, this is a tax on notional income, which is why it was so unpopular. It was described by one MP as “the most vexatious and oppressive tax”. Having said that, it would be wrong to trace the property-owning democracy back to the abolition of Schedule A alone. The teeth had already been taken out. Because rent controls were widespread, owner-occupiers paid tax at the rent-controlled value of their property, without suffering the loss of income from rent control that a landlord would. Furthermore, valuations were stuck at 1937 rates, due to rapid inflation in house prices during the Second World War that made revaluation politically controversial.3

Another big tax incentive was capital gains tax. When CGT was introduced in 1965 by Harold Wilson’s Labour government, it had an exemption for a person’s main home, something that still exists today. At the time, about 47% of people were homeowners, a sufficiently large bloc (many of them Labour voters or swing voters) that exposing them to CGT would be electorally troublesome, especially given that the Wilson government was governing with a tiny majority, which led to another election the next year.

There is a steelman argument in favour of the CGT exemption: it facilitates labour mobility, by enabling somebody to reinvest the proceeds from the sale of their house into buying a new one. But it quite clearly also acts as a subsidy for houses as an asset class: a sale of £500,000 of shares faces CGT, while a home worth £500,000 does not. This subsidy costs the government £31 billion per year.

There was also tax relief on mortgage interest. Originally, interest on all loans could be set against income tax, but this was ended in 1969 (under Labour) following one of Britain’s many fiscal crises – with the major exception of interest on mortgages. Unlike the other two, this tax incentive is no longer with us, having been abolished by Gordon Brown in 2000.

It’s also worth mentioning that, alongside these indirect subsidies, in 1967 the government introduced a direct subsidy for homeowners who did not earn enough to be able to set their mortgage payments against income tax.

In other words, in the 1960s three major tax incentives were created for owner-occupation. What is noteworthy is the degree of cross-party consensus. Schedule A was abolished under a Conservative government, while the CGT exemption and the maintenance of mortgage interest relief were Labour policies. It is hard to say exactly how much of an effect they had, but in the 1960s the homeownership rate went from about4 43% in 1960 to 51% in 1969.

Theme 2: Accessibility of mortgage lending

Tax policy in the 1960s, then, was stable and driven by consensus between the two main parties. The opposite was true when it comes to mortgages.

For a long time, mortgage lending was overwhelmingly dominated by building societies. Building societies were originally co-operative enterprises, whose members would pool together their savings in order to build or purchase housing. They were a curious concept. Unlike ordinary banks, they did not behave as profit-maximisers. They were mutual societies owned by their members, and saw their goal as being to provide their members with cheap mortgages at stable interest rates.

Until 1980, the building society industry effectively operated as a cartel. The Building Societies Association recommended an interest rate, and virtually all its members complied. But unlike a normal cartel, the building societies held interest rates artificially low and kept them artificially stable, with rates rarely adjusting to market conditions.

There was an obvious problem with this arrangement. If building society saving rates were substantially below market interest rates, then they would struggle to attract deposits, and would consequently have to ration access to the cheap, stable mortgage lending that they offered.

Up until 1964, this was not much of a problem, as interest rates broadly stayed low and stable. Over the next decade and a half, however, it ended up causing a financial crisis. What happened is best told by Samuel Watling, but in summary:

In the mid-1960s, the government forbade building societies from increasing their interest rates. This was part of a quixotic attempt to plug the country’s persistent trade deficit. The government could have devalued the pound (which, under the Bretton Woods system, had a fixed exchange rate), but did not wish to do this, partly out of national pride. It instead sought to reduce reliance on imports by reducing domestic demand, and here there was again a political constraint: reducing demand must not raise unemployment. In its infinite wisdom, the government instead enacted a wide range of wage and price controls, one of which was the ban on increased interest rates. At the same time, ordinary banks faced restrictions on their lending. Together, these measures led to severe rationing of mortgages.

Matters were made worse later on in the decade. Following slow growth, and the failure of its attempt to revitalise industry through economic planning, the government was forced to devalue the pound in 1967, but even that did not produce a trade surplus, and the next year the government had to embark on a programme of austerity, which included interest rate hikes.

But in 1970, the government changed, and performed a screeching U-turn on economic policy. Credit limits were abolished, and as the currency crisis abated, bank interest rates fell until there was no longer a disparity with the building societies. There was no longer a need for the rationing of mortgage credit. And in 1972, the Chancellor, Anthony Barber – the Liz Truss of his day – introduced a Budget containing a huge package of tax cuts and spending increases, targeting GDP growth of five per cent for the next two years.

The ‘Barber Boom’, however, overheated the economy. In 1973, to prevent inflation the government hiked interest rates by four percentage points to 11.5%, and reintroduced controls over bank lending. The building societies cartel, however, refused to raise their interest rates, given the harm that it would do to existing borrowers. As their interest rates were negative in real terms, savers pulled their money out, and consequently credit availability collapsed. The building societies were only saved by the stagflation of the late 1970s, which wiped out the real value of mortgage debt.

It is quite remarkable that the government was, on the one hand, handing out subsidies to homeowners through the tax system, while on the other, mortgage lending was subject to this feast-and-famine regime. Consistency was only restored under Thatcher. In 1986, the building societies were allowed to demutualise if more than 75% of their members agreed, which transformed their mission: rather than trying to lend at low, stable rates, they would now act like ordinary commercial banks. The artificial scarcity of mortgage credit caused by the building societies was ended.

Theme 3: Supply

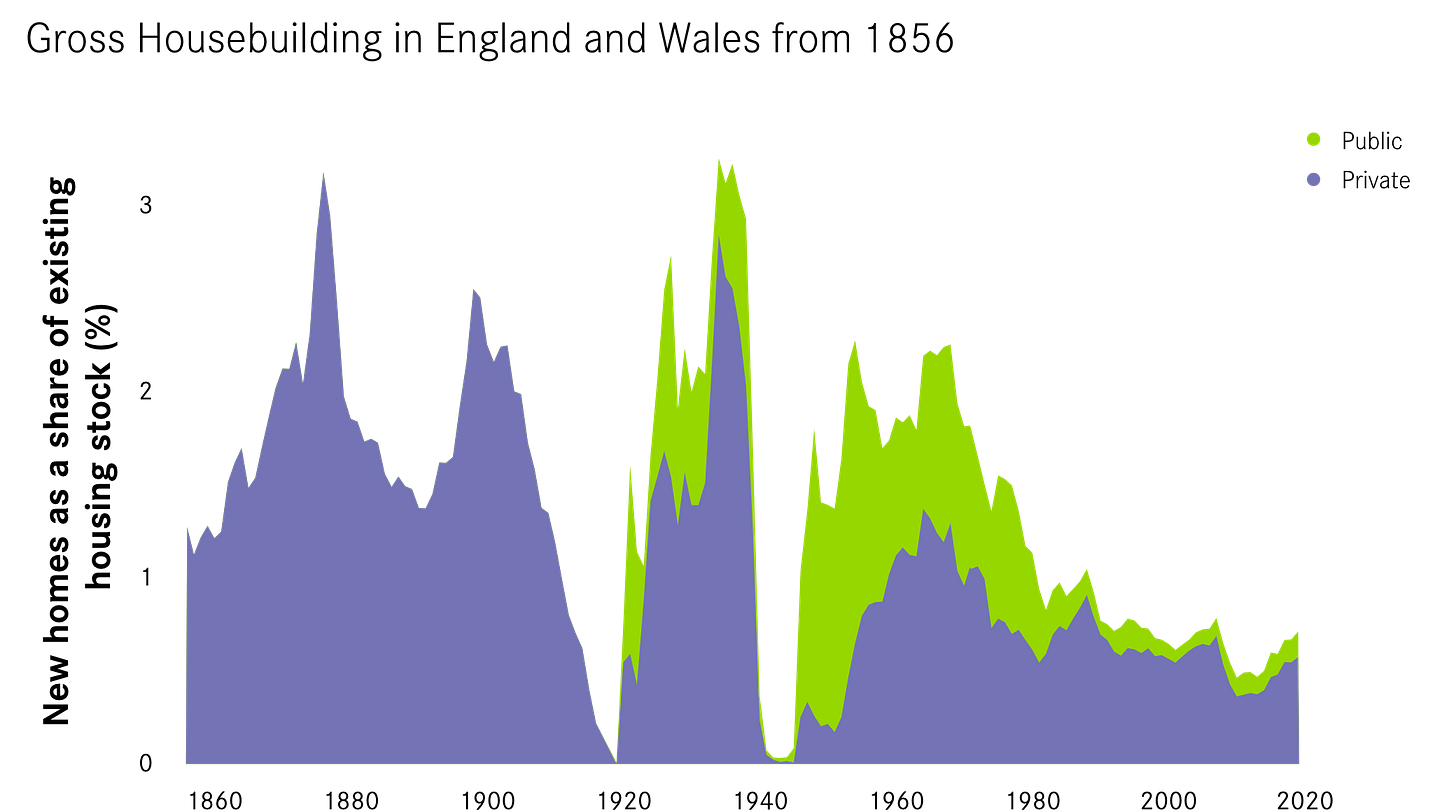

There were two great housebuilding booms in twentieth-century Britain. One was in the interwar period, especially the 1930s, and the other was from the late 1940s until about 1970.

The postwar boom was a mixture of public and private construction. The interwar boom was dominated by the private sector. And, unlike before the First World War, most of these homes were built for owner-occupation.

Why? The obvious answer might be rent controls. Rent controls were first introduced in 1915 as a ‘temporary’ measure for working-class dwellings only and, per Milton Friedman, they were not done away with until 1988. But although the wartime rent controls were extended in 1920 to virtually all existing dwellings, a major exemption was newly-built properties.

Clearly, then, rent controls cannot be directly responsible for all of the interwar houses built and immediately sold off to homeowners. But I suspect they are part of the story of the property-owning democracy in two, more subtle ways. First, thanks to the rent controls, landlords who were selling up would find it much easier to sell to an owner-occupier than to another landlord. Often, this would be the existing tenant: between 1914 and 1975, one in four transfers of privately rented dwellings to owner-occupation involved the tenant buying it off their landlord.

And second, the changes in supply might have been a second-order effect of rent controls. The housing market had become bifurcated. On the one hand you had cheap rent-controlled properties, whose rents were widely affordable. On the other hand, a newly-built rental property would be let at market rate, which would be unaffordable for the working class. Only the middle class would be able to afford it – but they preferred to buy, not to rent. The rational thing to do would be for property developers to build new properties for middle-class owner-occupation.

And certainly, there were more people able to afford to buy houses. The 1930s were a decade of relative affluence in Britain. (Our folk memory of the decade is extremely America-brained. Britain did suffer from the Great Depression, as did every country, but it was not nearly as severe as in America.) Wages were rising, and interest rates were stable, and a growing contingent of middle- and lower-middle class people were now able to afford to buy a newly-built suburban semi in Cheam or Solihull or Allerton. The interwar period was the mainspring of the property-owning democracy: one could say, only slightly facetiously, that it’s Stanley Baldwin’s Britain, and we’re just living in it.

The second building boom was in the postwar period. This involved less gross construction overall (and even less net construction, given the high rate of demolition of buildings considered to be slums). And it involved building considerably more social housing. But, contrary to the pervasive myth that we only built council housing in the postwar period, in most years, the majority of homes were built by the private sector.

Most of these were built for owner-occupation. Between 1939 and 1954 rent control was even more severe than it had previously been, applying as it did to new dwellings, but even after it was lifted there was no resurgence in building homes to rent. Squeezed by owner-occupation on the one hand, and council houses on the other, the private rental sector continued to decline: between 1951 and 1961, it went from 45% of the housing stock down to 25%.

The third supply shock was Right To Buy. Right To Buy is a scheme, introduced in 1980, by which council housing tenants have the right to buy their council home at a discount. This discount was substantial, initially between 33% and 50%, increasing to as much as 70% by 1986.

Right To Buy is probably the part of this story that is best known. It is central to the mythology of the Thatcher government. Over the course of the 1980s it brought millions of council-house dwellers from humble backgrounds into the fold of the property-owning democracy, as are borne out in the figures:

1961–1970: +7.88 percentage point increase in the proportion of owner-occupiers

1970–1980: +5.67 percentage points

1980–1990: +9.65 percentage points5

The ideology of the property-owning democracy

One way of pulling these threads together is as follows. In the interwar period, homeownership becomes more widespread, thanks largely to vast amounts of housing being built for owner-occupation, and also because rent controls cause landlords to sell to homeowners. This continues in the immediate postwar period. In the 1960s, homeowners are a large enough voting bloc that the government doles out a series of tax incentives to them. In spite of this, the mortgage market is chaotic in the 1960s and 1970s, which dampens demand. Under Thatcherism, supply of owner-occupied properties is massively increased through Right To Buy, and the deregulation of mortgage lending adds further fuel to the fire. By 1990, the seventy-year transformation of British society into a property-owning democracy is essentially complete.

Portrayed like this, the property-owning democracy sounds more like the result of impersonal forces rather than something planned. But it would be a mistake to think that the property-owning democracy was something that just happened. It has always had its advocates.

For the man who coined the term in the 1920s, the forgotten Tory MP Noel Skelton, mass property ownership was essential in an age of universal suffrage. Until 1918, there had been property qualifications for voting, which provided an in-built safeguard for Britain’s bourgeois democracy. But in 1918, suffrage was extended to all men and some women, and a decade later all other women gained the right to vote. There was the risk that the propertyless masses would vote for socialists and communists who sought to undermine private property. Democracy could lead to the destruction of capitalism.

Widespread property ownership would, however, allow democracy and capitalism to be reconciled with one another. It would legitimate the economic system, just as universal suffrage legitimated the political system. The many would be brought into the fold of capitalism.

The other argument in the property-owning democracy’s favour is what we could loosely call civic virtue. This point may seem slightly obscure to us, but it is nicely summed up in the famous remark that you could always tell the Right To Buy flats, because they were visibly better cared for.6 Property promotes responsibility, both for oneself and for one’s community. It (literally) gives people an investment, a stake, in their society. ‘Economics are the method: the object is to change the soul,’ as Margaret Thatcher once famously said.

Skelton’s ideas had little purchase on the Conservative Party until after the Second World War. Conservative politicians in the 1951–1964 made rhetorical commitments to it, and as we have seen the rhetoric led to policy too. But Skelton undoubtedly ‘won’ with Thatcherism. From this point on, the property-owning democracy was planned. Property ownership, as the 1987 Conservative Party manifesto said, gives one “power over [their life] in the most direct way” and “gives people a stake in society – something to conserve”. And as Thatcher herself put it at the 1986 Conservative Party conference:

In Scotland recently, I was present at the sale of the millionth council house: to a lovely family with two children, who can at last call their home their own. Now, let’s go for the second million! And what’s more, millions have already become shareholders. And soon there will be opportunities for millions more, in British Gas, British Airways, British Airports and Rolls-Royce.

…

The great political reform of the last century was to enable more and more people to have a vote. Now the great Tory reform of this century is to enable more and more people to own property. Popular capitalism is nothing less than a crusade to enfranchise the many in the economic life of the nation.

We Conservatives are returning power to the people.

Inspiring words indeed. But …

… was it a good idea?

To lay my cards on the table, I fully support a liberal capitalist economy. And I am extremely sympathetic to the goals of the property-owning democracy. Margaret Thatcher’s “crusade to enfranchise the many in the economic life of the nation” is, I think, morally right.

But I am concerned that the political economy of mass homeownership contains contradictions. The property-owning democracy contains dynamics which undermine itself.

The most obvious one is the electoral influence of homeowners. Imagine if the government tried to reintroduce the taxation on imputed rents. It probably should do this because, as any economist will tell you, to minimise their distortionary effect, taxes should be as broad-based and free from exemptions as possible. Refusing to tax the benefit in kind received by homeowners is economically distortionary. And yet, removing the exemption would be electoral suicide. As long as two-thirds of Britons are homeowners, and of the remaining third many aspire to be homeowners one day, subsidies are baked into the system.

There is also the opportunity cost of 40% of Britain’s household wealth being tied up in housing. Thanks to our inability to build enough homes, housing is essentially a non-productive, rent-seeking asset: it accumulates in value not thanks to any increase in the productive faculties of the nation, but due to artificial constraints on supply. And even if the housing supply were elastic, it is non-obvious that housing would be the most efficient allocation of capital.

These hidden subsidies and opportunity cost may be justified on their own terms as simply the price we pay for the property-owning democracy. But what is more perverse is the essential contradiction around risk. Property ownership does promote civic virtue, yes, but it also requires a tolerance for risk. Acquiring property comes with it the possibility that the asset might fall in value. And, in principle, making people less risk-averse is a good thing, given that capitalism depends on individual acts of risk-taking. If the property-owning democracy made citizens into risk-takers, then so much the better; not only would the mass property ownership engender popular support for capitalism, it would also fuel the engines of entrepreneurship.

But, if we are optimising for risk-taking, housing is the wrong asset to base a property-owning democracy on. An owner-occupied property is really three products bundled together.

It is a house, a place to live.

It is a home, a place in which people invest time, effort and emotion to make it feel theirs. A rental property is the first of these, and can also be the second, depending on how much choice the tenant has.

It is a financial product.

If you are a shareholder, and the stock market goes down in value, then you have lost money. If you are a homeowner, and the housing market crashes, then you have lost not just money but possibly also your house and your home. This creates substantial pressure on the government to de facto underwrite the housing market, as we saw in 2008.

It is ironic that all investment products in Britain have the mandatory disclaimer, ‘Capital at risk. The value of your investment may go down as well as up.’ – all investment products, that is, except for housing, the product into which most people pour most of their savings. We want to act as though property ownership is an unalloyed good, a house you can call a home that will also make you money. We do not want to think about the idea that it might decrease in value – and when it does, we call for help from the government.

But the most perverse effect of the property-owning democracy is NIMBYism. Some caution is needed here about the causal mechanism. I don’t think it is accurate to ascribe NIMBYism to a desire to protect property values, although that is probably in the mix. Instead, I think NIMBYism is more about an aversion to change. People moved to an area for a particular reason, and want to keep it that way: as the estate agent cliché goes, ‘location, location, location’. This impulse can apply to anybody, but because homeowners are more rooted, and have a greater financial stake in a particular location, they are generally more likely to want to stop housing construction than renters.

Without NIMBY institutions, NIMBY attitudes would mean nothing: people would grumble, but could not actually block anything. But we have (mostly independently from the property-owning democracy) developed NIMBY institutions, chiefly the planning system, and thanks to the electoral power of NIMBY attitudes, proposals to build a lot more housing are often doomed to fail, as we saw with the failure of the reforms proposed in 2020.

The enracinatory virtues engendered by the property-owning democracy are a vector for NIMBYism. And NIMBYism, by artificially increasing the cost of property, is undermining mass property ownership; undermining the property-owning democracy. And, even more worryingly, by holding back the country’s economy and making us poorer, NIMBYism is defeating the promise of capitalism.

Marx believed that capitalism contained the conditions for its own downfall, because it was ultimately based on the exploitation of labour. He was clearly wrong about this. But it is hard not to be a bit of a Marxist about the property-owning democracy. It clearly contains, if not the seeds for its own destruction, then at least an internal logic that undermines itself, and undermines the capitalist system that it seeks to protect.

Perhaps all the benefits of the property-owning democracy outweigh the costs. And perhaps there is a way around some of the political economy problems. Certainly, as Samuel Hughes has recently pointed out, whereas NIMBYism once worked to the advantage of property owners, it now works against them, because in cities like London they could make so much money if they were able to build more densely on their land. This gives me some hope that the internal dynamics will, ultimately, be pushed in the direction of YIMBYism.

But even YIMBYism might hit a bit of a brick wall. Plugging our housing shortage rapidly could cause a collapse in property prices, which is politically unacceptable. Fixing it slowly will not be much good at all, given the urgency of the housing crisis. Perhaps the least-bad option is to build just enough housing to keep house prices stable in nominal terms but falling in real terms. But that implies a high inflation rate, which is deeply unpopular with voters, as well as all the economic problems with it.

I do not know what the answer is. I do not know how we can reconcile these contradictions. But, unless an AI-induced economic transformation renders all existing economic questions redundant, the harsh political economy of the property-owning democracy will continue to undermine our country.

The term refers of course to all kinds of property, not just housing, but it is undeniable that Britain’s property-owning democracy has been built on housing not on shares.

Apparently the 10% figure appears in lots of papers that cite each other.

The parallels to today’s situtation in respect of council tax, whose valuations are stuck at 1991 levels, are striking.

Figures are not available for 1960. For 1961 the figure was 43.88%.

Liberalised mortgage rules undoubtedly contributed to some of this growth, but they were only introduced towards the end of the decade, and there is a clear jump after 1980.

I have seen this quotation attributed to Alan Clark, but I am unable to confirm exactly who said it.

I agree Skelton is almost totally overlooked these days, but I should flag up a good treatment by my former parliamentary colleague Dr David Torrance (if you can find a copy):

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Skelton-Property-Owning-Democracy-David-Torrance/dp/184954011X

Keynes and his Bloomsbury friends had various long-term leases that they would sometimes swap, some decades long. Concentrated ownership of land by the old aristocracy, again including some of their friends, seemed to be the underlying reason. The relative decline in that wealth post war--and the other reasons highlighted in this article--explain the decline in old money land holdings.