Between a rock and a hard case

Britain can’t build anything. How much are the courts to blame?

Every summer, without fail, traffic grinds to a halt on the A303 near Stonehenge. The road, the main artery linking London with the South West, is mostly dual carriageway, but it goes down to a single carriageway around the stones. It struggles to cope with the traffic at the best of times, but the influx of holidaymakers means there are always tailbacks around Stonehenge in the summer months.

The traffic is bad in itself, but it also makes the experience of visiting one of the most important prehistoric archaeological sites in the entire world much worse. The road goes about 200 m from the stones. Celebrating the Winter Solstice is ruined thanks to the headlights. For all these reasons, there have been many proposals to bypass the road since the 1970s. The most recent of these was developed in the late 2010s, and for a while everything was going well. In spite of its astronomical price tag of £1.7 bn for a 3.3 km-long tunnel, it got Treasury support in early 2020, and was granted planning permission in late 2020 – but no spades ever got in the ground, and the Labour government cancelled it in 2024.

The Stonehenge tunnel is a textbook example of Britain’s inability to build anything. And one of the reasons it failed was that it was subject to a successful judicial review in mid 2021.1 Judicial review, universally known as JR, is the process by which government decisions can be challenged in court on the basis that they are illegal. There is a perception that JR is one of the major reasons that Britain cannot build anything – in fact, that it is one of the reasons that the government is incapable of getting anything done.

This post is about whether this perception is correct. I think both that it isn’t, and at the same time it is.

On the one hand, it is important to remember that JR is not really law, but metalaw, the process by which the law is enforced. In the Stonehenge case, the law said that the Secretary of State for Transport had to follow a particular process before granting planning permission, a process which was not precisely followed. The process is, however, fiddly and complicated, which means there are lots of places where the Secretary of State could make a legal slip. Really, the fault lay ultimately not with the institution of JR, but rather with the underlying law that it was enforcing.

I think that this view is correct, but inadequate. It is probably closest to the view held by most lawyers, who would say that JR is a vital means of maintaining the rule of law. By all accounts, the rule of law demands that the government should follow the law – and if the law is bad, Parliament should change it, not the government ignore it. Although it is easy to forget – England had the rule of law long before she had democracy or liberalism,2 so we have the luxury of taking it for granted – the rule of law is what prevents the arbitrary, despotic exercise of State power. It is civilisational.

But lofty invocations of the spectre of tyranny can easily distract from the fundamental truth: JR is not about preventing a repeat of the Stuart kings, but is instead a process by which minor procedural slip-ups can be weaponised by opponents who, having lost in the argument in the political arena, want a second bite at the apple in the courts. This is not just an issue with the underlying process, but also the way in which it is enforced. JR, actually, is the problem.

What JR is – and isn’t

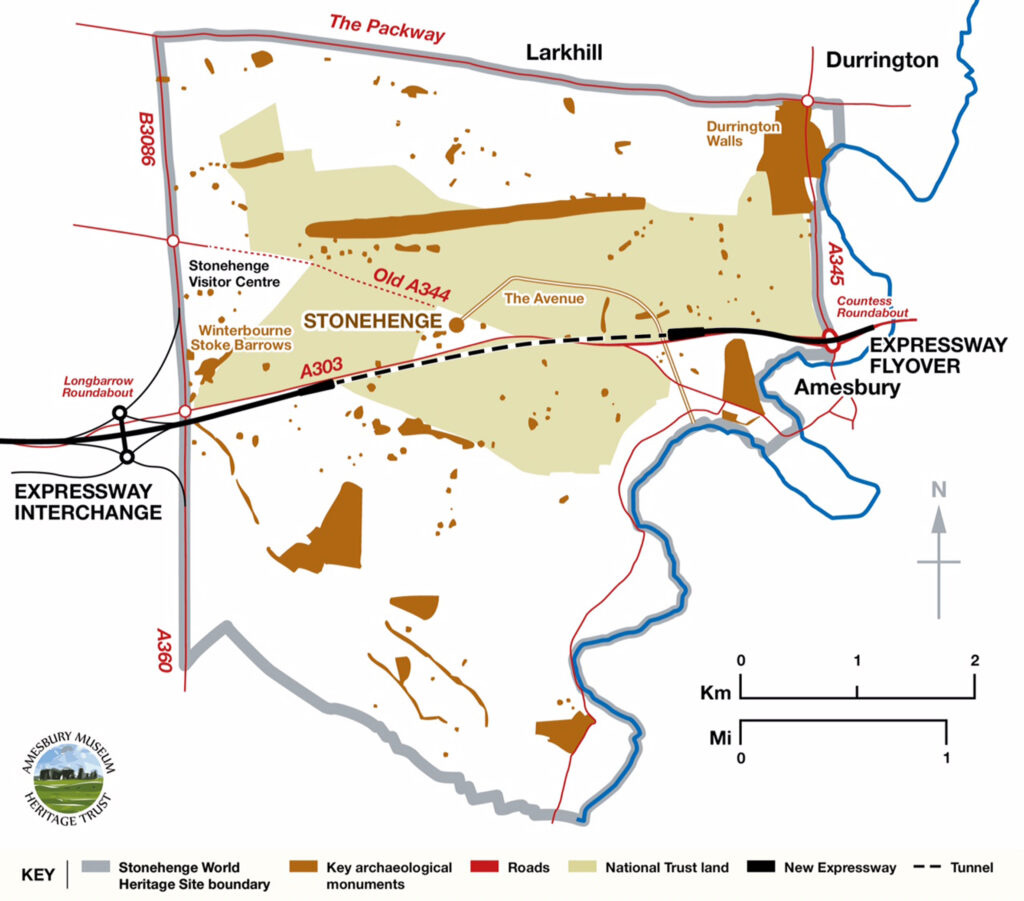

The Stonehenge World Heritage Site is much wider than just the stone circle. It includes much of the landscape around it, in which there are thousands of archaeological monuments, many of them Neolithic burial mounds.

The proposed tunnel would be bored too deep to have any effect on the archaeology of the site. The controversy was instead around the entrances to the tunnel, known as the portals, and there was concern that they would disturb archaeological artefacts. The Stonehenge landscape also appears to have been deliberately designed for ritualistic purposes, and the portals would, as the scheme’s planning inspectors put it,

introduce a greater physical change to the Stonehenge landscape than has occurred in its 6,000 years as a place of widely acknowledged human significance. Moreover, the change would be permanent and irreversible.

For what it’s worth, I am quite sympathetic to the political cause of the opponents of the tunnel: given that Stonehenge is a uniquely significant and precious site, a longer tunnel would seem to be more appropriate. But that is an entirely separate question from the legal arguments, and from the underlying fact that the opponents were able to conduct their campaign in the courts.

The claimants challenged the decision of the Secretary of State for Transport in late 2020 to grant a ‘Development Consent Order’ to the scheme. A DCO is meant to be a ‘one-stop shop’ for permission for major infrastructure projects: it gives the project planning permission, environmental approval, listed building consent, and so forth.

The scope of JR is potentially massive. Any “decision, action or failure to act in relation to the exercise of a public function”3 can be challenged by JR. Most obviously, this means that acts of central and local government, as well as QUANGOs, are amenable to JR, but its net can trap some non-State bodies as well – the Advertising Standards Authority, for instance.4 What matters is not who is exercising the power, but the nature of the power. If it is a ‘public function’, its exercise can in principle be subject to JR.

This makes it sound like everything could get JR’d. There are, however, several things that prevent it from placing all statecraft into the hands of the courts.

Parliamentary sovereignty – an Act of Parliament cannot be struck down by a court.

The courts are reluctant to interfere in matters of ‘high politics’, like foreign policy, the use of public funds, or the substantive content of government policy.5

Time limits:6 a JR claim must be made within three months, or six weeks if it concerns planning, compared with the standard six years for most civil claims.

JR is a last resort, only when other remedies (like a planning appeals process, or an ombudsman) have already been exhausted.

That still leaves a lot of scope for challenge. It certainly includes every decision to grant planning permission to an infrastructure project.

When deciding a JR claim, the purpose of the court is in nearly all cases not to assess the scheme on its merits. The decision to grant the DCO in respect of this scheme is a balancing act, between the benefits to drivers, the improved setting of Stonehenge, and the increased safety of dual carriageways on the one hand; and the financial costs, and the environmental and heritage impact of the road on the other. How this balance is struck is essentially a political question, and the court is not attempting to make the decision on behalf of the Secretary of State: the court is neither equipped to do so, and nor does it have the democratic mandate to do so legitimately.

Instead, as the court put it itself, with emphasis added:7

Judicial review is the means of ensuring that public bodies act within the limits of their legal powers and in accordance with the relevant procedures and legal principles governing the exercise of their decision-making functions. The role of the court in judicial review is concerned with resolving questions of law. The court is not responsible for making political, social, or economic choices. Those decisions, and those choices, are ones that Parliament has entrusted to ministers and other public bodies. The choices may be matters of legitimate public debate, but they are not matters for the court to determine. The court is only concerned with the legal issues raised by the claimant as to whether the defendant [i.e. the Secretary of State for Transport] has acted unlawfully.

The claimants therefore challenged the DCO not on the merits of the scheme, but on the basis that the Secretary of State had not followed the law. They had five separate grounds of challenge, five separate legal errors allegedly made when granting the DCO. They were successful on one of the four subgrounds of Ground 1 and on one of the three subgrounds of Ground 5, and failed on the rest.8

The legal arguments were complicated and technical, as is apparent from the fact that there were subgrounds of challenge, and from the judgment’s 38,000-word length. I will focus on the two subgrounds that succeeded.

One of them concerned whether the Secretary of State had properly considered the scheme’s impact on heritage assets. Within 2 km of the proposed road scheme, there are 255 scheduled monuments, 229 listed buildings, and 8 conservation areas. There are also 1142 other heritage assets within 500 m of the scheme.

The question was whether the Secretary of State had taken into account the scheme’s impact on all of these heritage assets, as he was required to do. The scheme’s Environmental Statement and Heritage Impact Assessment had, in fact, considered this. But there was a problem – the Secretary of State was not provided with these documents when making his decision. He had been provided with a report by a panel of planning inspectors, which summarised the impact on some of the assets, but not the full, comprehensive reports.

The law is not stupid (at least, not here). It does not require a minister to understand every single minutia relevant to their decision. But they do need to be provided with a précis of the relevant parts, or a briefing from officials, neither of which was forthcoming in this case. The Secretary of State should have been adequately briefed on all the matters which he was legally required to take into account when making his decision.

In other words, this was a procedural question. If the law says that such-and-such a factor must be taken into account, and it is not taken into account (whether in good faith or not – and there was no suggestion of bad faith in this case), then the decision is a nullity.

Put another way, the Stonehenge Tunnel was struck down by a court because a civil servant failed to put a piece of paper on the minister’s desk.

The other ground which succeeded was that the Secretary of State had failed to consider the merits of two alternative schemes which would reduce the impact on the World Heritage Site.

The courts have often considered9 when it is appropriate for possible alternative sites to be taken into account in the planning process. In general, the fact that ‘it could be built elsewhere’ is irrelevant. But there are some exceptional circumstances where alternative sites must be taken into account, in particular where an alternative is so “obviously material” that it must be considered.10

These were held to be such circumstances, given the scale of the engineering works, and the fact that they would be taking place within possibly the most historically important site in Britain. Furthermore, the two mooted alternatives were serious options which used essentially the same route. This does not mean the court said that the Secretary of State had to approve one of the alternatives – that would, again, involve the court’s making the decision on his behalf. Instead, his duty to act as a rational decision-maker meant he had to give the alternatives due consideration.

The court therefore overturned the Secretary of State’s decision.

This did not have to mean that the scheme was dead. The government re-ran the process, and granted another DCO in 2023 for a scheme that was materially the same. There was an attempt at another legal challenge, but it was dismissed in early 2024.11 But by this point, an election was looming, and owing to increased costs the tunnel was finally cancelled by Rachel Reeves in mid 2024. It is probably fair to say that, if the 2021 claim had not succeeded, the tunnel would currently be under construction.

JR is not the problem

This was a very unusual case, for one reason – it succeeded. As of May 2024,12 there had been:

137 DCOs, of which 34 have been challenged in court by JR.

Four of the challenges concerned a refusal of the DCO. Two of them succeeded.

The remaining 30 involved a challenge to the Secretary of State’s granting of a DCO. Of those 30, only four succeeded, and in only two of those cases was the decision to grant the DCO actually overturned by the court.13

So, 4% of DCOs are successfully challenged by the court – and (albeit with a small sample size), your chances of winning are much better if you are a developer challenging refusal rather than a NIMBY challenging approval.

The reason for this is quite simple: the government typically does its homework and follows its processes, and the courts are very unwilling to interfere with matters of political judgement. NIMBYs (and disappointed developers) can try to challenge all they like – but they are unlikely to win.

Seen this way, the problem is that courts are having their time wasted on unmeritorious JR claims. The answer to this is various procedural tweaks to stop these claims in their tracks, which is what has been recommended to the government by a review conducted by the Conservative peer and planning barrister Lord Banner KC.

Even when the claimants do win, as in the Stonehenge case, it is unclear that JR is at fault. The fault lies instead with Britain’s involuted process for giving planning permission to Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects.14

Although deeply flawed, the process is clearly an improvement over the old system of multi-year, open-ended public inquiries, in which both the details of the scheme and the need for it in principle would be up for debate. Instead, the process proceeds in stages. First the government sets out its policy saying, for instance, that there is a need in principle for a bypass of the A303 near Stonehenge. The government is (with a few exceptions15) then required to grant DCOs in accordance with that policy, following an examination by planning inspectors according to a rigid timetable. This means that the big picture and the details of the scheme are kept procedurally separate.

But every stage of the complicated process provides an opportunity for legal error to be made by the decision-maker, an opportunity for NIMBYs to find a possible mistake to hang their challenge on. In the Stonehenge case, the claimants had a total of ten grounds and subgrounds, and only needed to succeed on one of them to stop the scheme. In the face of the high failure rate, this is possibly why it is still rational for NIMBYs to launch JRs. Throw enough at the wall, and some of it might stick.

According to this conventional view, then, the answer is to tweak the JR process, so that it is harder for NIMBYs to bring claims that are doomed to fail; and to reform the procedure for infrastructure approvals, so there are fewer hooks on which NIMBYs can hang their challenges in the first place.

To this, we might add regulating legal crowdfunding, which is a common means for NIMBY groups to raise funds for these legal challenges. And reforming our implementation of the Aarhus Convention: even though the default position in litigation is that the loser pays the winner’s legal costs, Aarhus means that NIMBYs who lose a challenge often only have to pay £5,000 or £10,000 of the government’s costs.

All of these are sensible, technocratic fixes. And, if this were the totality of the solution, then there would be an implicit assumption that there is nothing fundamentally wrong with JR. But …

… JR itself actually is part of the problem

According to the court in the Stonehenge case, JR is not about the merits of the decision. The court is concerned merely with legal questions, and ensuring that public functions are exercised in accordance with the law.

But of course, JR is about the merits of the decision. ‘Save Stonehenge World Heritage Site’ did not bring the challenge out of sheer love of the rules. They are not an organisation of legalistic pedants. The clue is in the name: they brought the challenge because (in their own words) they want to save the Stonehenge World Heritage Site. They are bringing the challenge because they disagree with the merits of the decision, and are using JR as a means to that end.

In other words, JR is fulfilling two very different user needs. The user need of the court (if you can call it that) is to uphold the rule of law. The user need of the claimant is to try to put a stop to a decision. For the court, law is law; for the claimant, law is politics by other means.

I think that the overriding objective of JR should not be upholding the rule of law, but instead enabling good government. At least as far as government is concerned, the rule of law ought to be a means to an end, not an end in itself.

I do not think that JR enables good government. Lawyers, defending JR, often say that it is ‘prophylactic’: the threat of JR improves the quality of decision-making. In fact, the effect is often iatrogenic. The fact that attempts at JR have become standard practice by NIMBY campaign groups leads to defensive practices by civil servants who (understandably) do not wish to have their compliance with the law scrutinised in court. In an effort to make sure every single part of the decision-making trail is documented, the paperwork multiplies to show that The Rules Have Been Followed. The name of the Civil Service’s guide to avoiding JR, The Judge Over Your Shoulder, is instructive: public servants should be able to make decisions according to their understanding of the best interests of the country without members of the judiciary metaphorically peering at them from over the bench.

There is also a deep moral problem with JR. There is a concept in the academic literature on democracy known as loser’s consent: at its most basic, democracy requires that the loser of an election accepts its result.16 The practice of holding elections is not the hallmark that a country is functioning as a democracy; instead, it is the concession speech at 3am in the morning of election night in the drab setting of a provincial leisure centre. We can easily extend this concept to all political decisions. If the government decides that a railway or a road or a power station or a reservoir gets built, then the loser has to accept that that decision is final. I do not take issue with Save Stonehenge World Heritage Site’s political campaigning – as mentioned above, I have sympathy with them. What I disagree with is the fact that the system enables them to use law to re-run the political battle.

But more fundamentally, I am not sure that the conceptual framework of JR is suited to the problems of government. A JR involves a court’s answering just one question – ‘was the law followed?’ – and its answer trumps all other considerations. The purpose of the court is not to weigh up the costs and the benefits of finding the decision illegal:17 the court’s calculus ignores whether delaying (and ultimately cancelling) the construction of the Stonehenge Tunnel is a price worth paying to ensure that The Rules are followed. It does not consider the opportunity costs involved with its decision.

In court, the rule of law is a kind of absolutism, in the sense of something that conquers all other important values. The law is a trump card. If it is legal – you win. If it is illegal – you lose.

This is the correct function of a court. It should restrict itself to legal questions. In a criminal trial, a court should not be weighing up the social costs and benefits of finding the offender guilty: either he is guilty or not. In a commercial context, the law should not be pushed aside simply because the court thinks there is a public interest in finding a contract invalid. For a variety of reasons,18 The Rules need to be given primacy in both these contexts.

But in the context of public law (the branch of law which governs the State) I don’t think that this is the right way of looking at things.

‘Politics’ is often a dirty word – it’s common to hear (ironically) politicians say that it is ‘time to put politics aside’ in the service of some wider cause. Although it is true that the practice of politics can often be grubby and hair-tearingly illogical, politics is simply a way in which we make decisions that affect our common future. It is the means by which the community delegates the power to make those decisions to its representatives.

Judges ought not to get involved with politics. Partly, this is because the courts are not a democratic institution. Nobody voted for judges, and nor are they responsible to an elected institution like Parliament – and that is how it should be. For the courts to trespass on the authority of elected officials would be wrong. We would be substituting the rule of the people for the rule of lawyers.

But even in an autocracy, it would still be wrong for judges to usurp the role of politicians. Political decisions are made in the context of difficult, value-laden and often uncertain trade offs. The decision whether to build a new road near Stonehenge requires balancing convenience to motorists and economic growth against environmental impacts and monetary cost. This is not well-suited to being decided by judges. A trial is not an inquiry, but instead an adversarial process, each side trying to put forward its strongest case, which does not lend itself well to divining where the balance lies between different factors. And the degree of weight assigned to each factor is essentially a subjective decision: reasonable people can, for instance, have a wide variety of opinions on how much we should value nature versus economic growth. The balance cannot be struck by judges. Their expertise lies in the rational, objective process of taking a set of legal rules and applying them with reason and logic to a factual situation.

Defenders of the system would argue in response that the courts already recognise this, hence why they concern themselves with questions of law alone, and never with the merits of a decision: they stay out of politics. But I would say two things to this.

First, JR, as it currently works, forces political decisions into a legal straitjacket. Even if the process is wholly legal, even if the finest legal minds in the country are deciding applications for judicial review strictly on the basis of law, the Stonehenge case only came to court because the NIMBYs wanted it to. The case is political and its outcome is political however much we dress it up in legal robes.

But more importantly, following The Rules should not always be the most important consideration: what is more important is that the State is able to act competently. The Rules should be enforced to the extent that they enable this but no further. At least as far as infrastructure is concerned, the State should be able to act decisively and rapidly, according to its assessment of where the public interest lies. Public law ought to further this end, not hinder it.

For the State needs all the help it can get. There are many reasons that Britain does not build enough infrastructure: it is expensive, and we currently do not have money to spend. It carries trade offs, and we do not want to reckon with them. It requires a belief in the future, and the future has lost its allure. But when the will and the money can be found, we make things unnecessarily difficult for ourselves, forcing schemes through paperwork, consultations, processes and finally into court. The law ought to be trying to help us push the cart up the hill, not imposing roadblocks along the way.

R (Save Stonehenge World Heritage Site) v Secretary of State for Transport [2021] EWHC 2161 (Admin).

The existence of the rule of law was sealed in the English Civil War, which put to bed the idea that the King could exercise power arbitrarily, but its roots date back to the medieval period.

Britain became something that looks like a modern democracy some time between 1832 and 1928, depending on how much weight you place on universal suffrage, equally-sized Parliamentary constituencies, and the ability of unelected aristocrats to veto legislation outright. Liberalism was a doctrine that had become cemented as our governing ideology by the mid-19th century, although its roots date back to the late seventeenth century.

R v Advertising Standards Authority, ex p Insurance Services Ltd (1990) 2 Admin LR 77. The case was decided in part because, if the ASA had not arisen as an industry-led initiative, Parliament would probably have needed to establish a regulator. The powers it exercised were therefore public in nature. See also R v Panel on Takeovers and Mergers, ex p Datafin Plc [1987] QB 815.

See in particular Council of Civil Service Unions v Minister for the Civil Service [1985] AC 374, 411 per Lord Diplock.

Stonehenge at [19], quoting from R (Rights: Community: Action) v Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government [2021] PTSR 553 at [6].

The judge gave short shrift to some of these arguments: “With respect, there is nothing in this point.” at [151] and “Mr Wolfe [the barrister] has not shown the court any authority [i.e. piece of case law] where that has been accepted.” at [215].

See R (Mount Cook Land Ltd) v Westminster City Council [2003] EWCA Civ 1346; Derbyshire Dales District Council v Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government [2009] EWHC 1729 (Admin).

See Derbyshire Dales, [16] to [28].

R (Save Stonehenge World Heritage Site Ltd) v Secretary of State for Transport [2024] EWHC 339 (Admin).

The other two decisions were quashed by consent of the parties.

These were introduced by the Planning Act 2008.

See the Planning Act 2008, s 104(4)–(8) for the exceptions.

Subject, of course, to the ability to challenge the election result on the grounds that it was unfair in some way.

The court does take costs and benefits into account to some extent when it comes to remedies. In the Stonehenge case the remedy was a quashing order: the decision was declared a nullity and had to be re-taken. It is open to the court not to grant a quashing order, and instead grant another remedy.

In the commercial context, commercial certainty should override the exigencies of the situation.

In the criminal context, there is similarly an overriding public interest in ensuring that we punish the guilty even though we may feel sorry for them. Even more importantly, the twin foundations of the criminal law – the presumption of innocence, and the standard of proof beyond reasonable doubt – together entail that the prosecution should strictly follow the rules.

This is a really great explanation of JR and how it affects govt operations and delivery of DCOs.

One potential problem with the idea that JRs should aim to enable good government (as opposed to upholding the law) is this could mean the definition of “good government” itself becomes a decision for the courts. This could lead to more JRs, and maybe more successful JRs. (e.g., if rules were only enforced “to the extent that they enable [the State to act competently in the public interest]” then anything could be challenged claiming it wasn’t in the public interest.)

Unfortunately, the better solution is parliament changing bad laws to make process-following easier and more aligned with the public interest.

Great piece. What should we do instead?